The Printed Image: Cecil Ffrench Salkeld and ‘Red Barbara’

The Printed Image returns in 2024 by taking a closer look at one of the illustrated books that entered the public domain earlier this month; Liam O’Flaherty’s Red Barbara and Other Stories, illustrated by Cecil Ffrench Salkeld, published in 1928. This book is not only included in Falvey Library’s Special Collections, but the entirety can be read in the Digital Library.

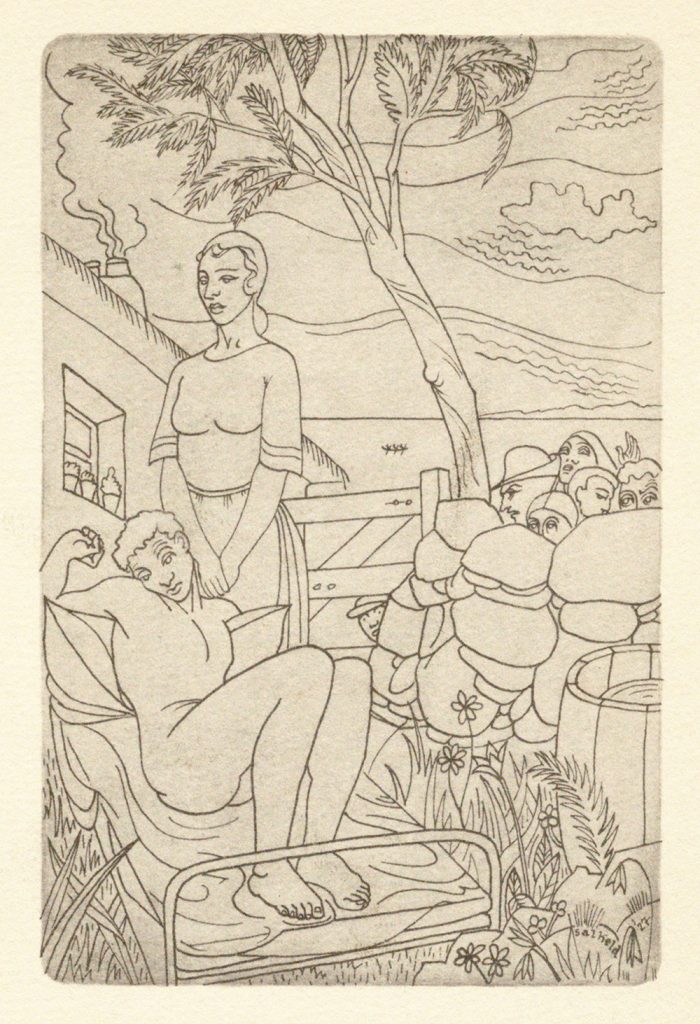

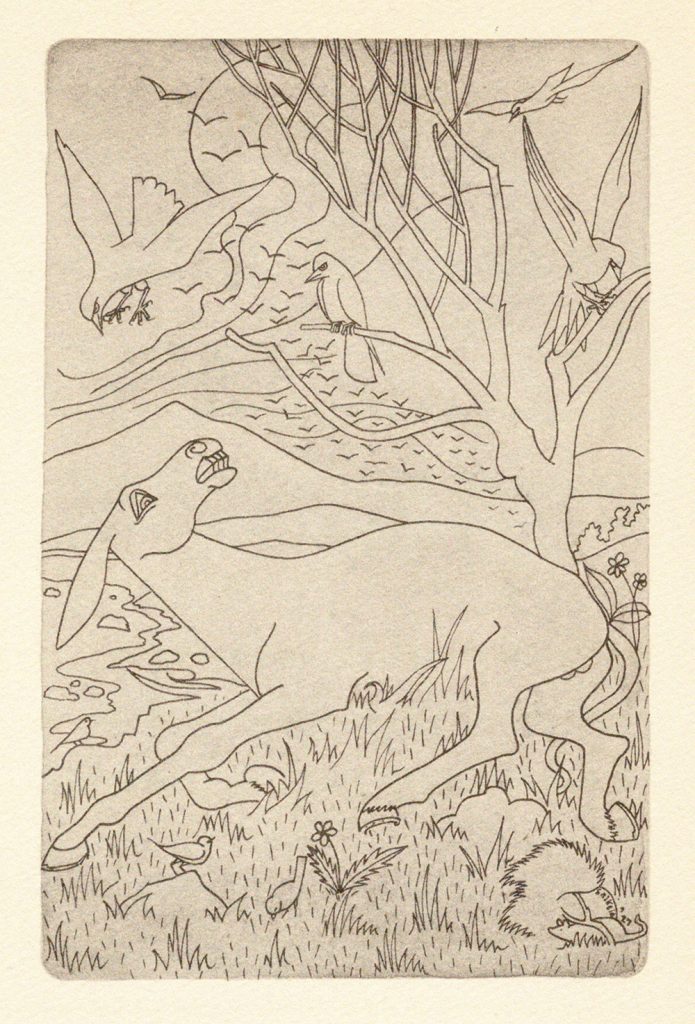

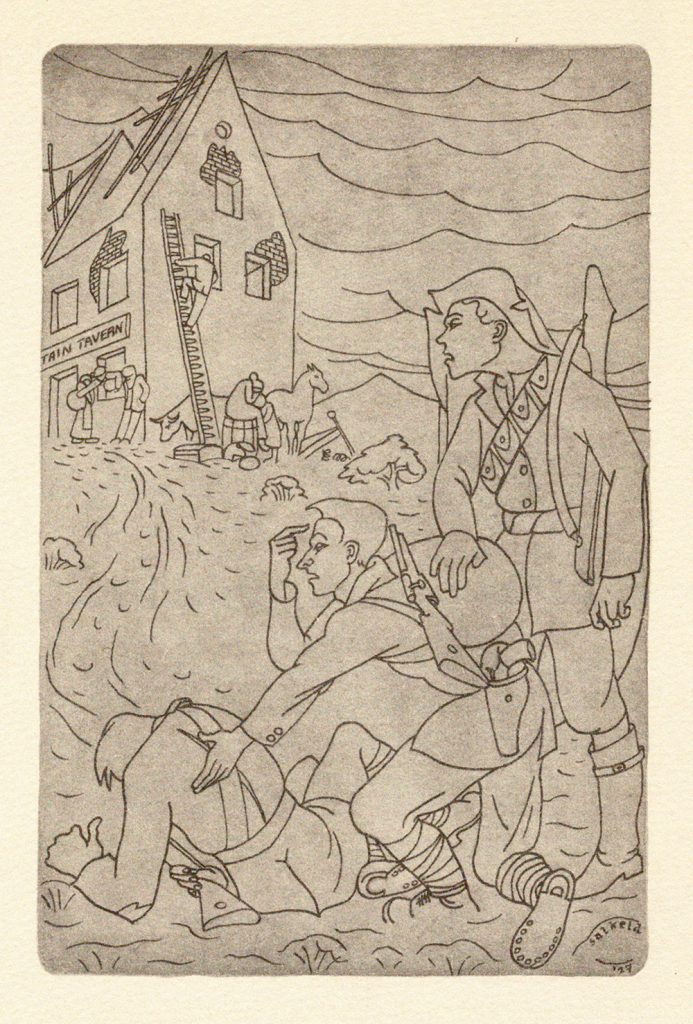

The book contains four of O’Flaherty’s short stories, each one accompanied by a Salkeld illustration. Salkeld uses a sharp, clean line in the illustrations, with a unique stylization based upon the shape and form of the figures and the environment; there is no rendering or shading to add further definition to the subjects, just the essentials. While there may not be a unifying visual element among the four illustrations, there is a quality of menace that recurs through the images, from the crowd of onlookers in Red Barbara to the stormy ocean waves of The Oar.

I could not confirm how the original illustrations were made, but the quality of the line suggests pen-and-ink drawing. However, Salkeld also worked in printmaking, so it’s possible the original art could have been made through etching, a line engraving, or a lithographic process. The gray wash of the illustrations even resembles an etching plate or lithographic stone. The printed illustrations in the book itself rest on the surface of the textured paper without any evidence of pressing or indentation, so it’s likely that the book was produced by an offset printing method, by the printing house of William Edwin Rudge in Mount Vernon, New York.

Though Cecil Ffrench Salkeld may seem to be an obscure figure nowadays, he was an active participant in the artistic and literary life of Dublin in the 20th century. Born in 1904 to Irish parents in India, his mother Blanaid, herself a poet, actress, and translator, returned to Ireland with Cecil in 1910 upon her husband’s death. Cecil entered the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art at the age of 15 and continued his studies in Germany at the Kassell Kunstschule, before having his first solo show in 1924 at the Dublin Painter’s Gallery. [1]

From 1937 to 1946 Cecil and Blanaid operated the Gayfield Press, which highlighted and supported writers within the Dublin literary scene. He was a co-founder of the Irish National Ballet School, with ballet and dancers serving as subjects for many of his paintings. A mural he painted for Davy Byrne’s pub can still be seen today, a locale made famous by its inclusion in James Joyce’s Ulysses. Finally, his daughter Beatrice was married to the writer Brendan Behan, and Cecil served as the basis for the character of Michael Byrne in Flann O’Brien’s At Swim Two Birds. [2]

Red Barbara can be viewed in the Rare Book Room by appointment or in the Digital Library. To learn more about Blanaid Salkeld and her role with the Gayfield Press, please visit The Irish Times. To learn more about the history and development of offset printing, please visit Prepressure.

Sources

[1] “Cecil Ffrench Salkeld ARHA 1904 – 1969, Irish Artist.” Adams.ie, www.adams.ie/irish-artist-directory/cecil-ffrench-salkeld-arha-art-sold-at-auction.

[2] “Cecil Ffrench Salkeld.” Wikipedia, 21 Nov. 2023, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cecil_Ffrench_Salkeld.

Mike Sgier is a Distinctive Collections Coordinator at Falvey Library.

Rebecca Oviedo is Distinctive Collections Librarian/Archivist at Falvey Memorial Library.

Rebecca Oviedo is Distinctive Collections Librarian/Archivist at Falvey Memorial Library.