The Printed Image: The Red Rose Girls

This March installment of The Printed Image highlights works in the Digital Library and circulating collection by a trio of illustrators from the ‘Golden Age of Illustration’ who also have a personal connection to Villanova, Pennsylvania. Elizabeth Shippen Green, Violet Oakley, and Jessie Willcox Smith each enjoyed enormous success and popularity in art and illustration, and resided at the Red Rose Inn from 1901 to 1906, a private residence off of Spring Mill Road that still stands to this day.

Nicknamed ‘The Red Rose Girls’ by their mentor and teacher Howard Pyle, the trio met in Pyle’s illustration class at the Drexel Institute in 1897 and soon shared a studio space at 1523 Chestnut Street in Philadelphia. After spending time in Bryn Mawr and finding city life an increasing distraction from their work, they soon leased the Red Rose Inn, joined by Henrietta Cozens, who would tend to the house and gardens of the estate. At a time when professional opportunities for women were narrowly defined, and which were expected to be abandoned once they were married, the Red Rose Girls’ arrangement was practically revolutionary, creating a space where they could thrive in their artistic and professional careers, outside of the bounds of the normative gender expectations of the day.

With the Red Rose Inn set to be sold in 1906, their lease expired and the group was forced to move to an estate in the Mount Airy neighborhood of Philadelphia, nicknamed ‘Cogslea’. Once marriage entered into the picture for Elizabeth Shippen Green in 1911, the living arrangements of the group would fluctuate, and while they would continue to remain close, the creative and personal alliance found at the Red Rose Inn would not remain the same. [1]

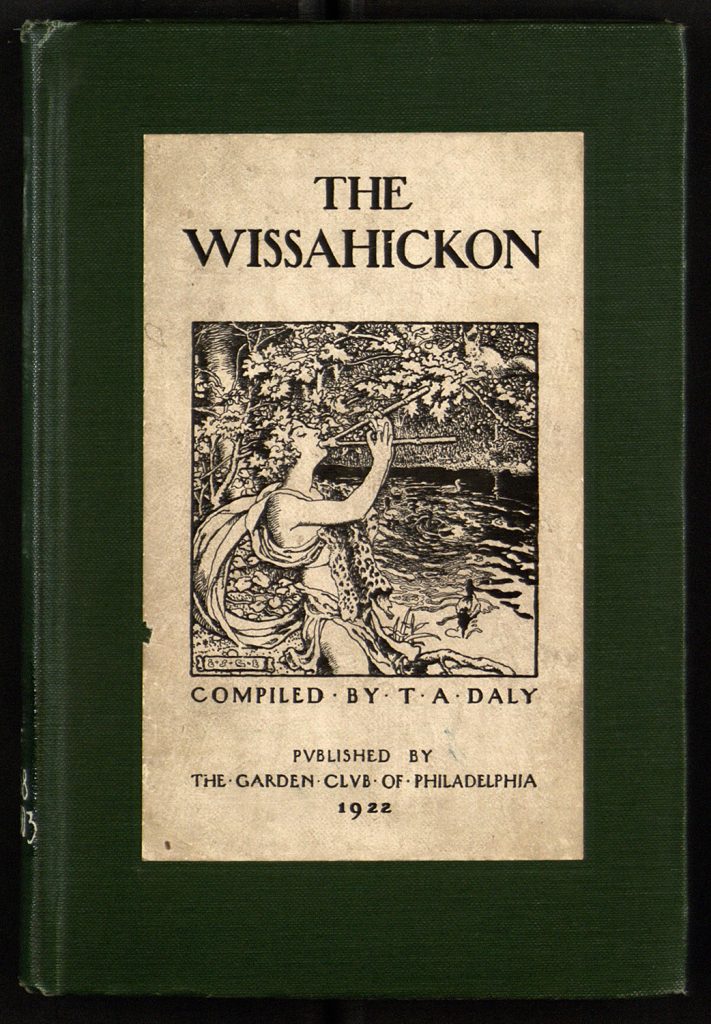

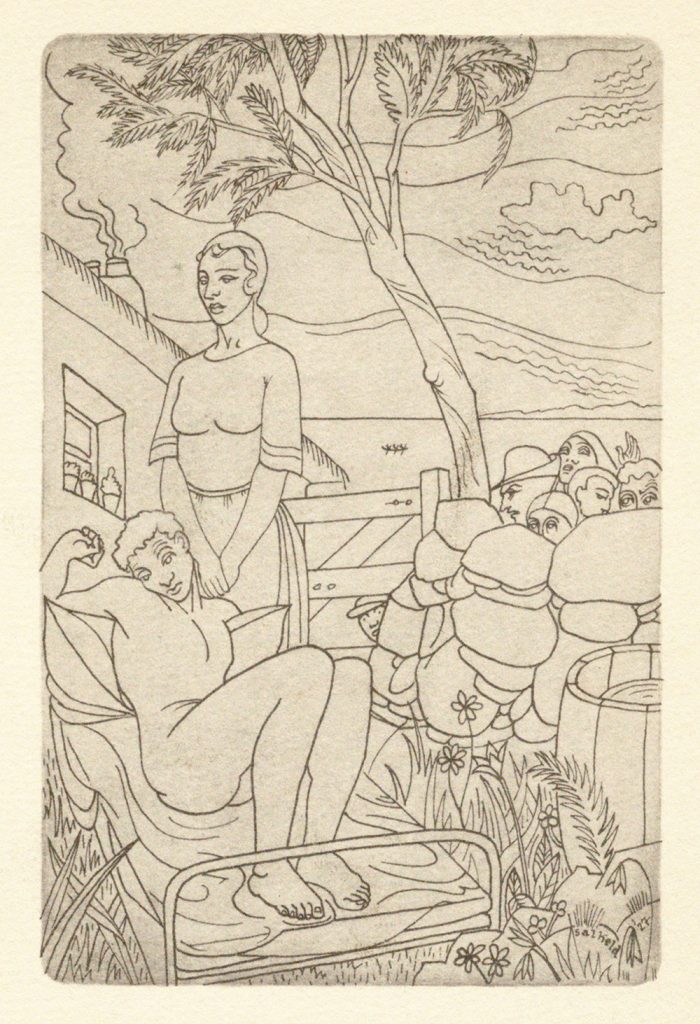

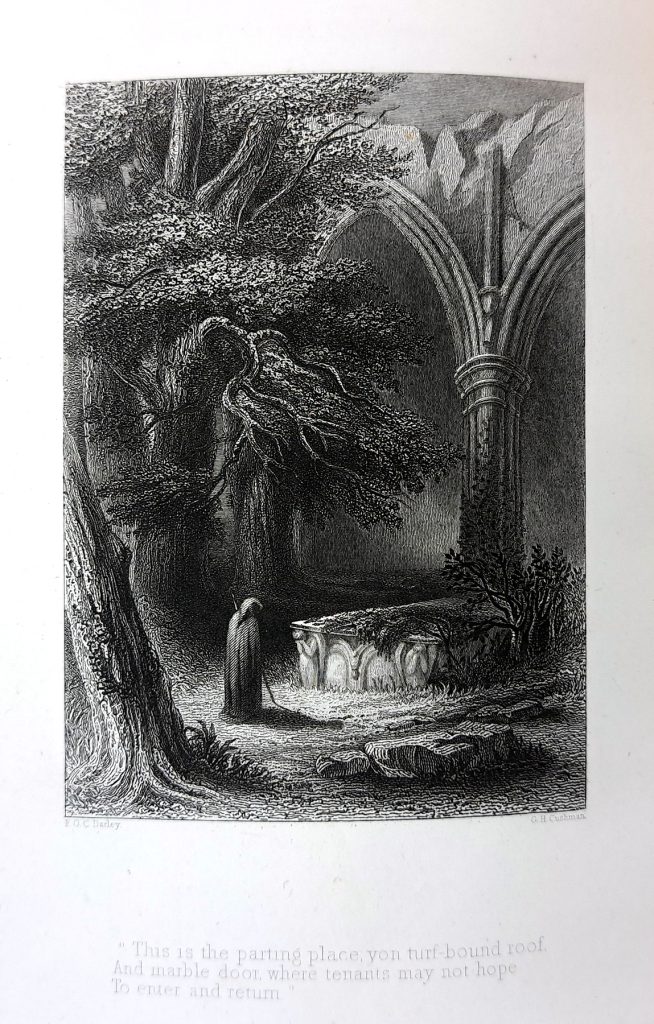

Elizabeth Shippen Green-Elliott – Cover for The Wissahickon

Included in both Special Collections and the Digital Library, this small volume about the Wissahickon Park in northwest Philadelphia includes a black-and-white cover by Green. The cover displays the lush, bucolic style found within many of Green’s paintings and illustrations, influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites and Romantics.

As the publication year and signature on the cover may imply, this illustration was made after Green’s marriage to Huger Elliott, an architect and instructor who would work at the Rhode Island School of Design, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, and the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Arts. Contradicting the conventional wisdom of the day, Green was able to continue her illustration career after marrying Elliott, maintaining her contract with Harper’s and illustrating 19 books, all while attending to her domestic and social responsibilities as Mrs. Huger Elliott. [1, pg. 194]

Violet Oakley – The Public Ledger, February 5, 1928

Newly added to the Digital Library, this issue of the Public Ledger includes a photographic reproduction of a medal designed by Oakley for the Philadelphia Award, which was created and sponsored by author and editor Edward W. Bok.

This was not Oakley’s only public commission within Pennsylvania. Earlier in 1906, Oakley would debut one of her most high profile commissions, a set of murals recounting the history of William Penn for the Governor’s Reception Room at the State Capitol in Harrisburg, which are still on display to the public. The murals were critical to her career as a muralist and enjoyed enormous popularity, though they were not without their critics. These murals would be followed by commissions for the State Senate and Supreme Court Chambers, completed in 1919 and 1927 respectively.

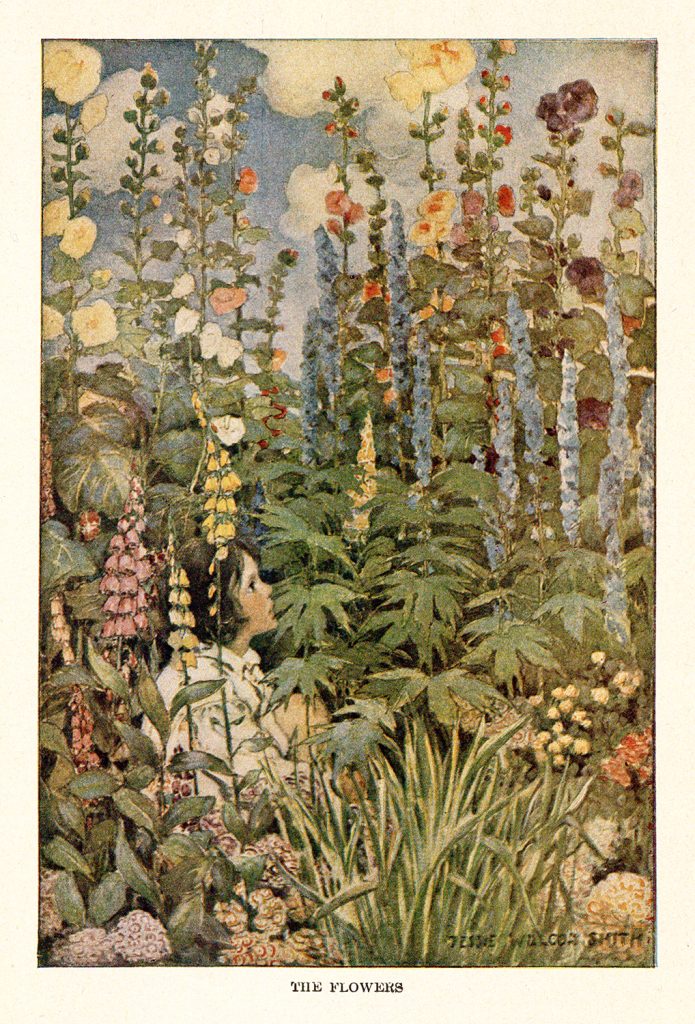

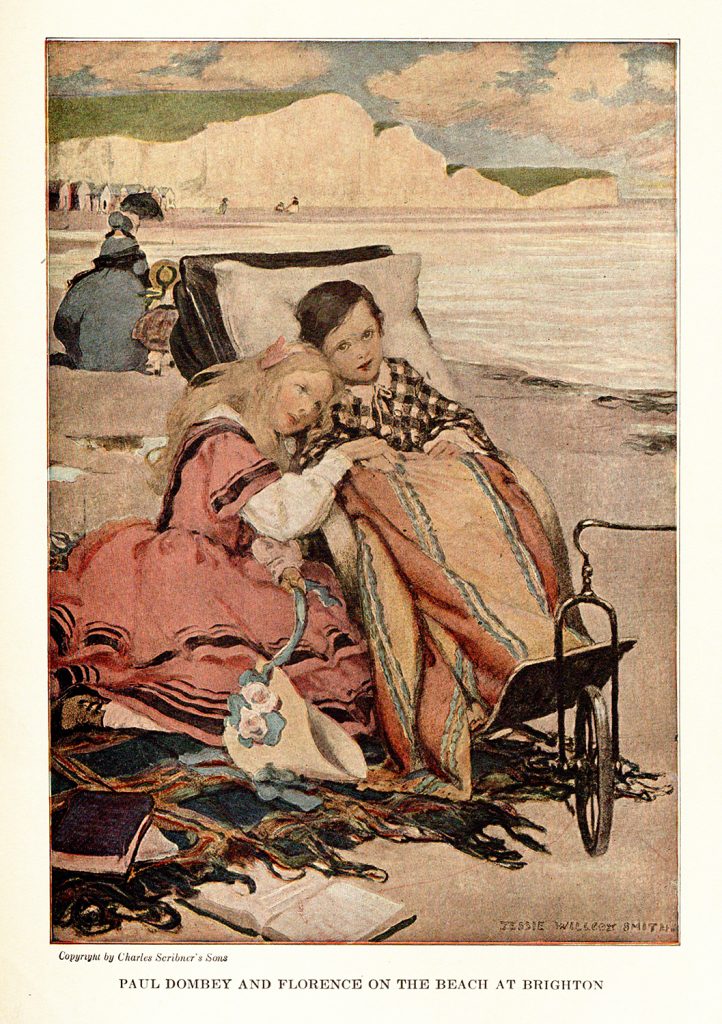

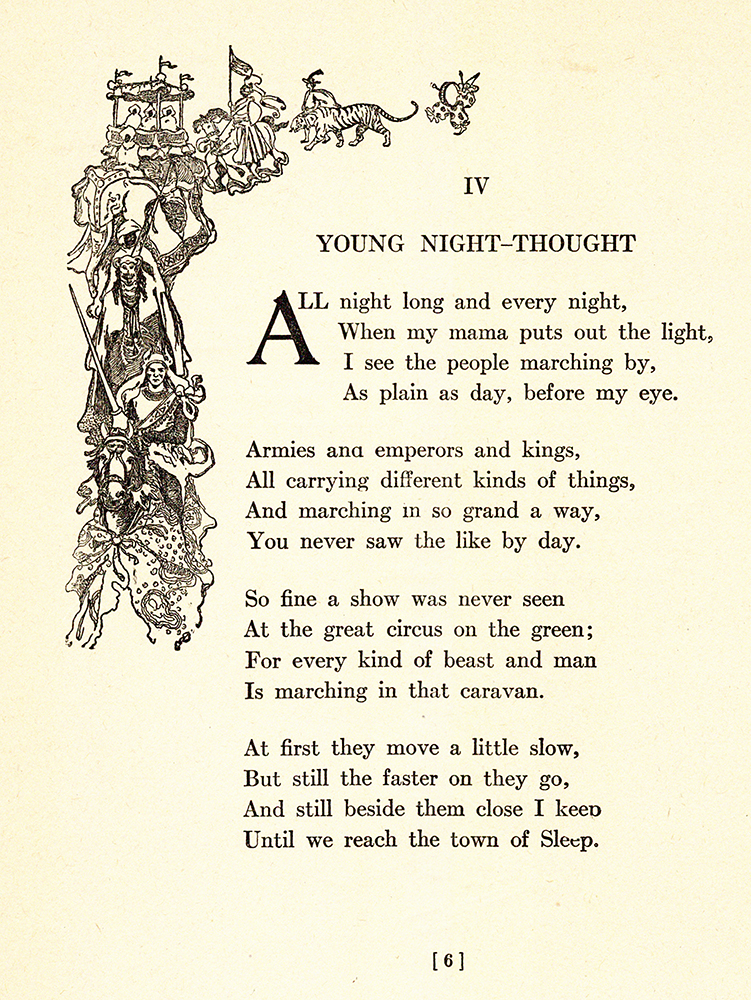

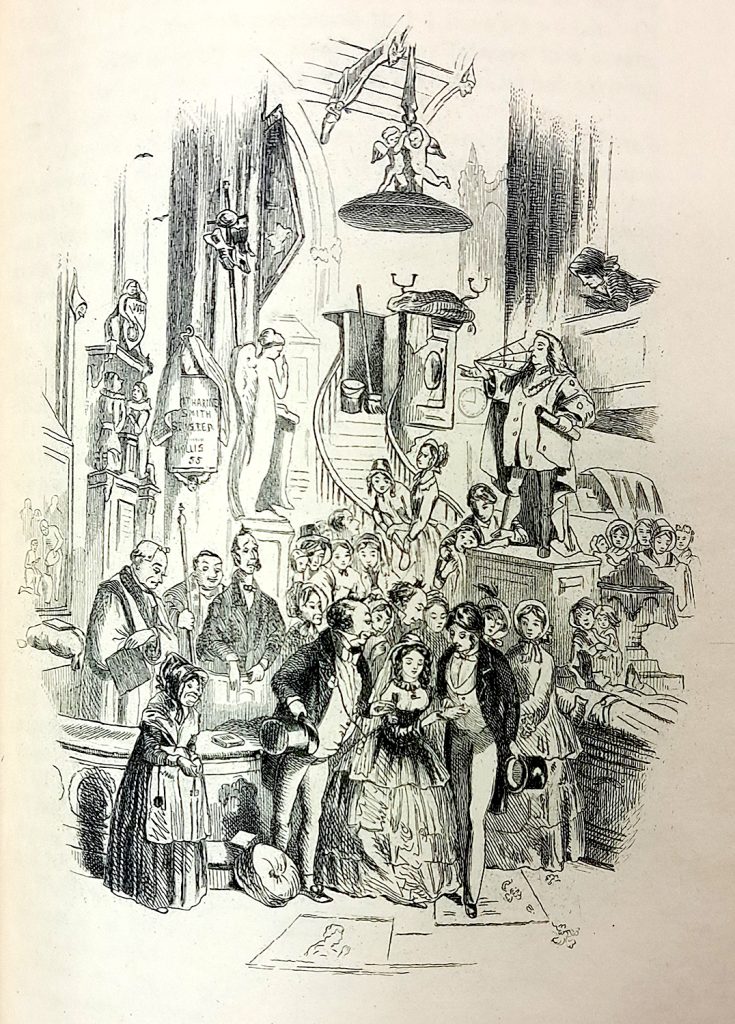

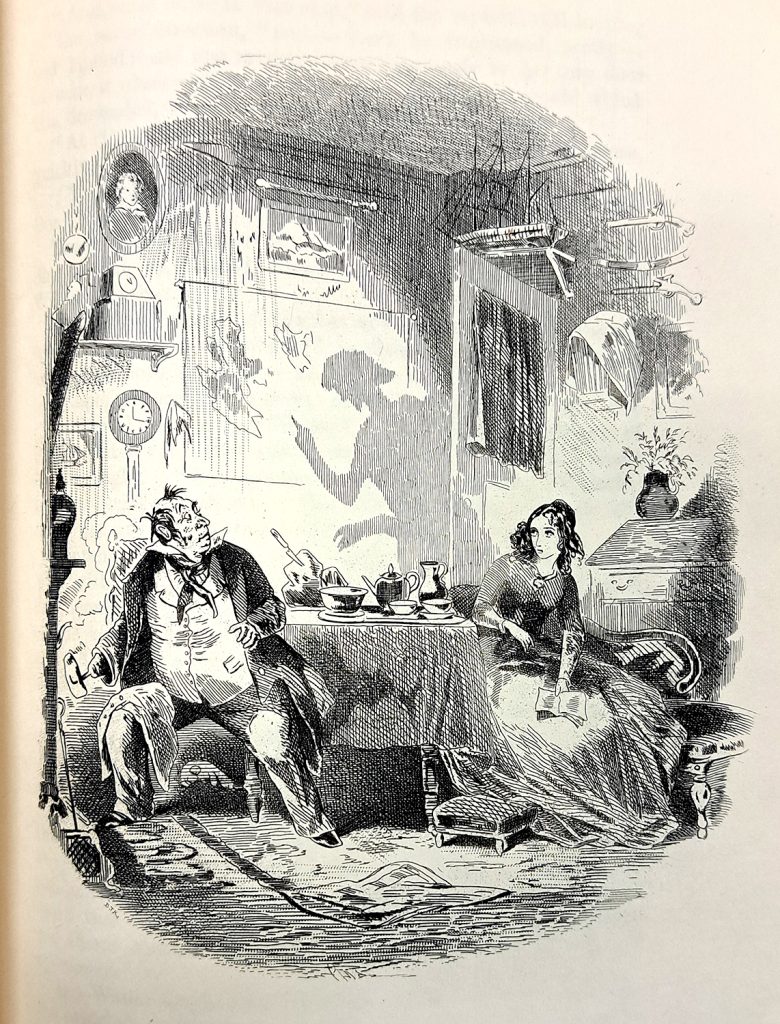

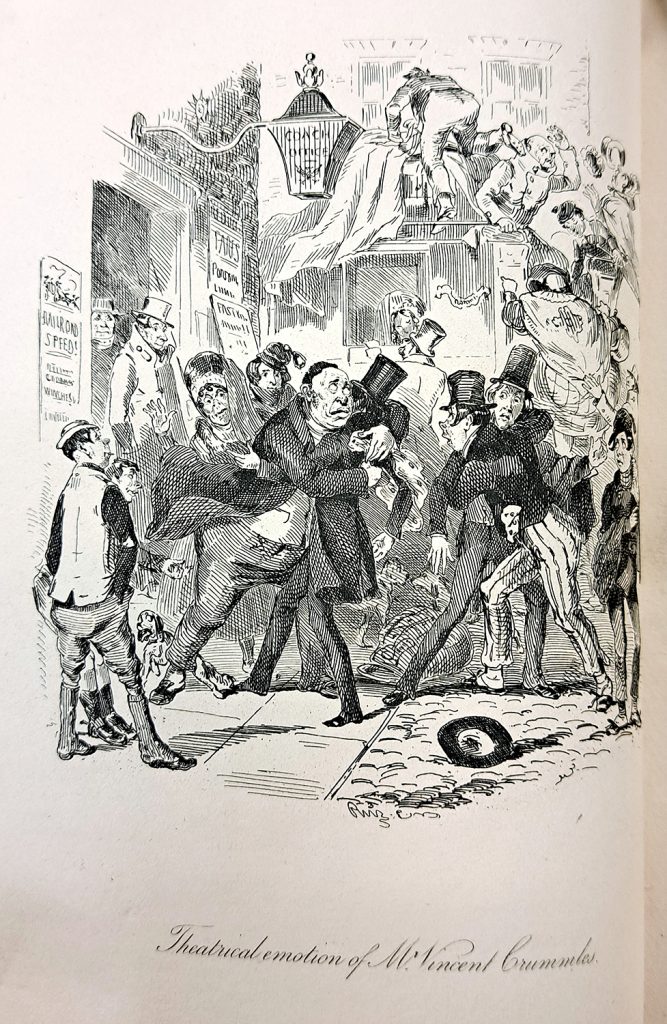

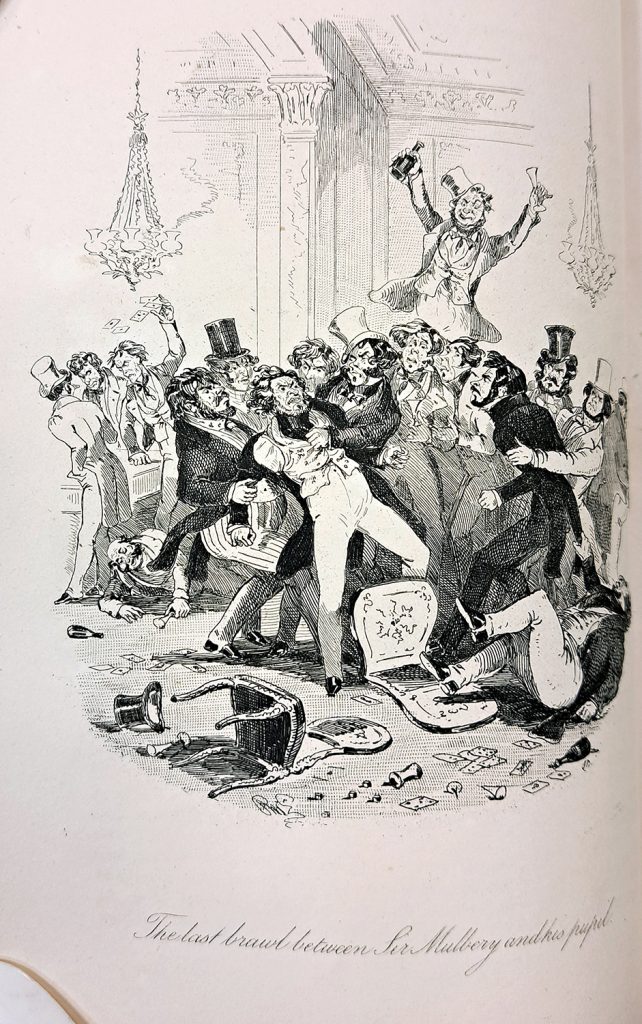

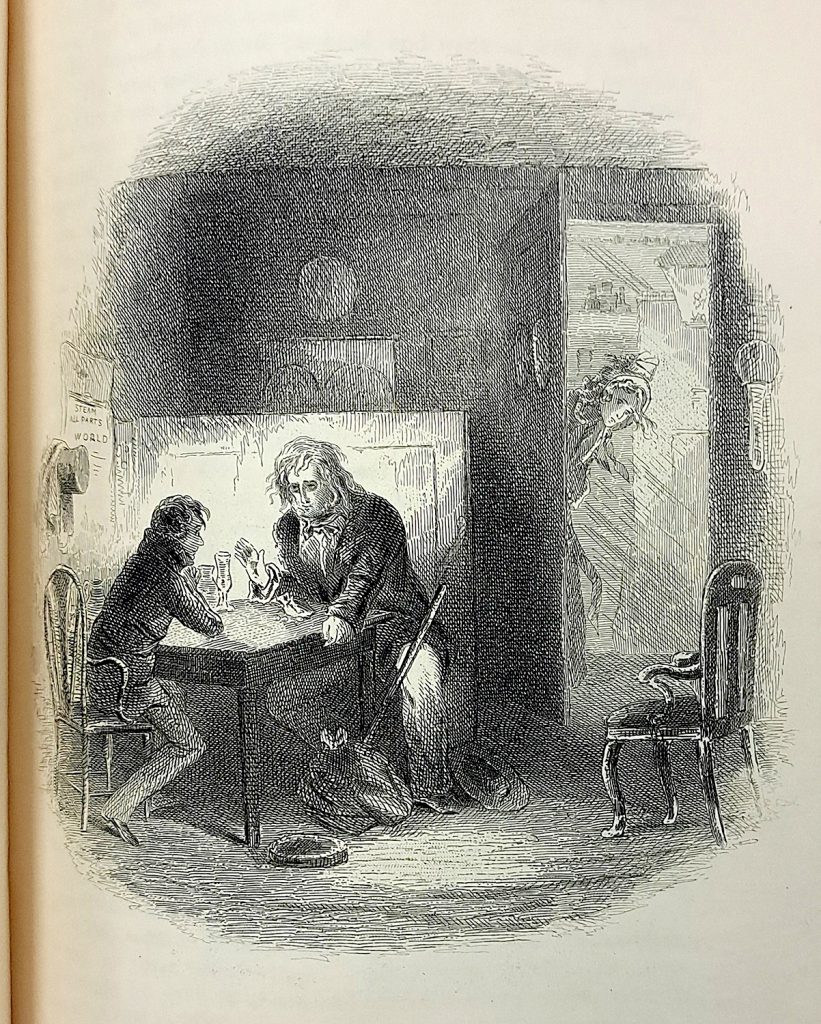

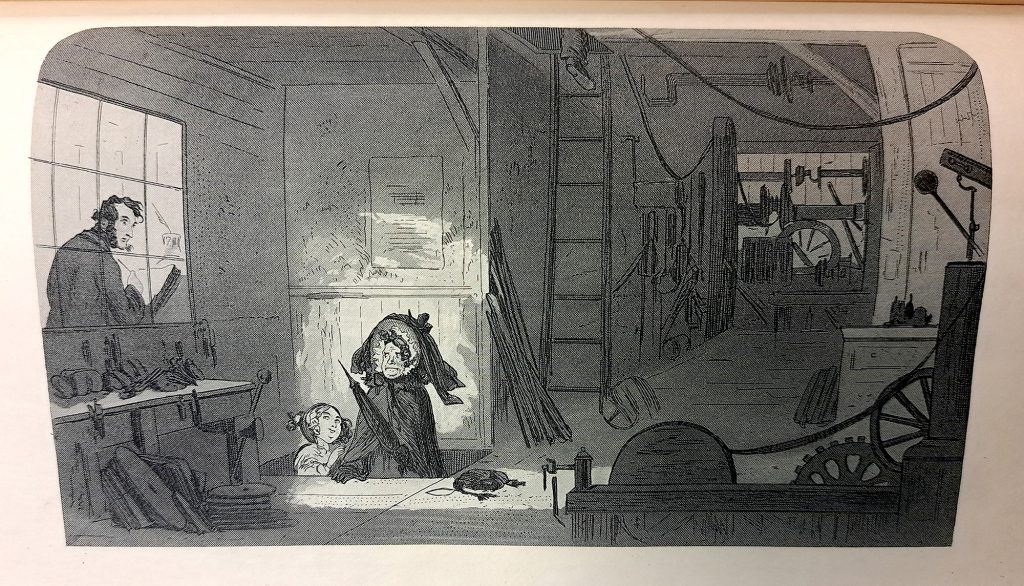

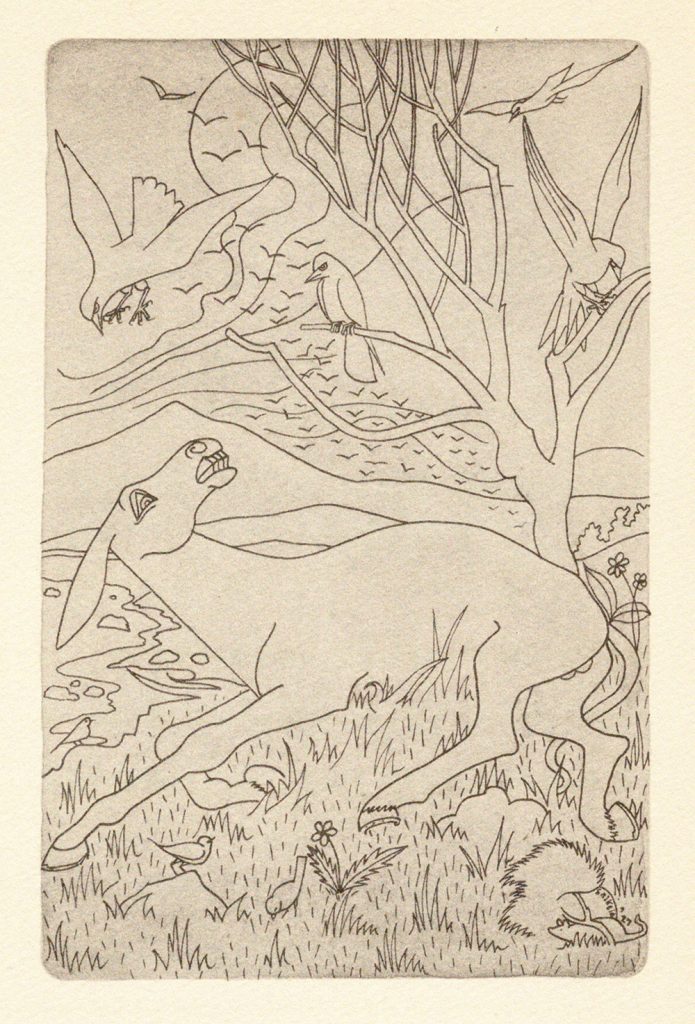

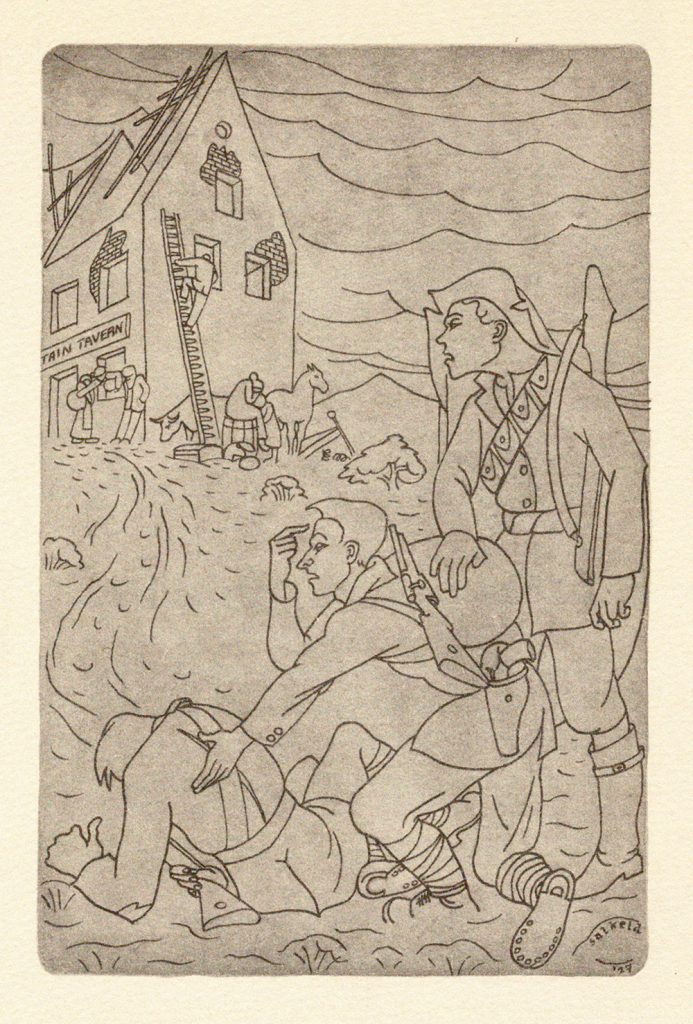

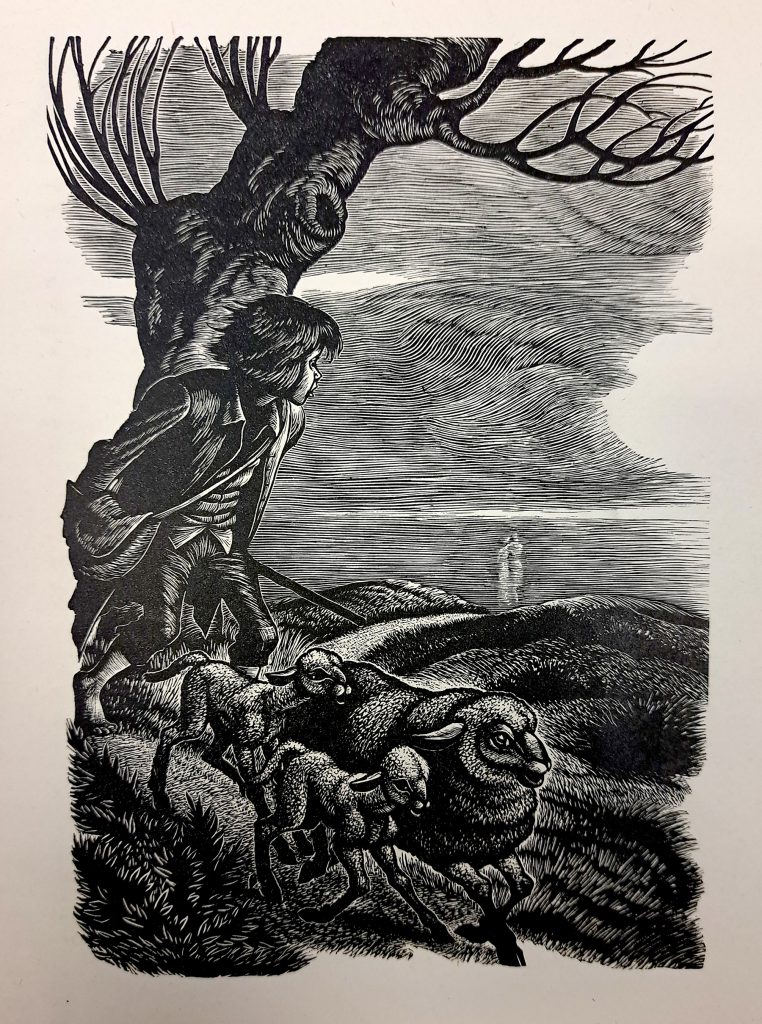

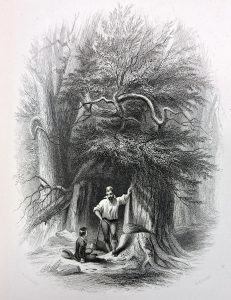

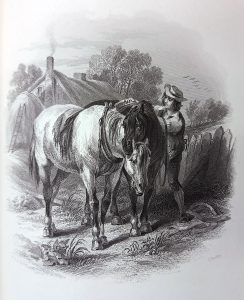

Jessie Willcox Smith – A Child’s Garden of Verses and The Children of Dickens

The eldest of the Red Rose Girls, Smith is represented in the library’s circulating collections in two books: A Child’s Garden of Verses by Robert Louis Stevenson (1905) and The Children of Dickens by Samuel McChord Crothers (1925). Her illustrations for both works display her trademark styles; children as subjects, realistic environments, and detailed costuming. But there is also a sense of idealism within them, a style referred to as ‘romantic realism’ by professor Mark W. Sullivan [2], where the imaginative world of a child is given precedence and legitimacy.

Smith found enormous success in publishing, with clients such as Harper’s, Collier’s, Scribner’s, Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, and illustrations for over 60 books. In 1991, she was the third woman inducted into the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame, followed by Green in 1994 and Oakley in 1996. Of the original Red Rose Girls, only Smith and Cozens would remain together as companions and partners, until Smith’s death in 1935. [3]

You can learn more about the works of Green, Oakley, and Smith in the book The Red Rose Girls: An Uncommon Story of Art and Love by Alice A. Carter, as well as Carter’s interview with the Illustration Department podcast, and in an essay by Villanova professor Mark W. Sullivan for The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.

Mike Sgier is a Distinctive Collections Coordinator at Falvey Library.

References

[1] Carter, Alice A. The Red Rose Girls : An Uncommon Story of Art and Love. New York, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2000.

[2] Sullivan, Mark W. “Red Rose Girls.” The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, 2015, philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/red-rose-girls/.

[3] “Jessie Willcox Smith.” Wikipedia, 31 Oct. 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jessie_Willcox_Smith.