Joseph E. Hernandez, Class of 1885

“Friendship.”

We recently digitized an interesting autograph album that was compiled by Joseph Everal Hernandez, a student at Villanova College in the 1880s. Hernandez wrote a poem at the beginning of the album “to my friends” in which he begins:

When years elapse,

It may, perhaps,

Delight us to review these scraps,

And live again ‘mid scenes so gay…

The following pages in the album hold prose, poetry, and art by Hernandez’s friends and family, as well as possibly a few teachers, primarily from his time at Villanova. Some of the names appear more than once.

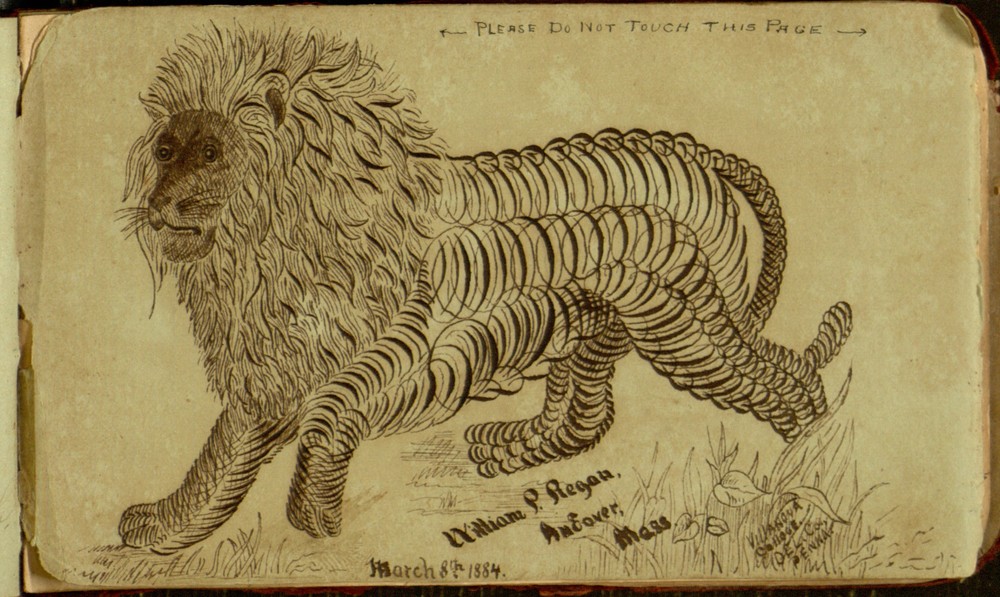

“Please do not touch this page.” (We touched it to digitize it!)

The artwork includes several pen-and-ink drawings, as well as a few paintings. Two particularly lovely paintings by Hernandez’s classmate James Harkins of Atlantic City, New Jersey, depict a red-and-white striped lighthouse and a house beside a river.

Many entries are dated, with years ranging from 1882 to 1887, and most note what seems to be the author’s hometown. Hernandez was from St. Augustine, Florida, and there are some names from that locale, in addition to his friends from Villanova.

Painting of a lighthouse, signed by Jas. A Harkins.

Looking through the Villanova College catalogues that we have digitized from the 1880s, I was able to trace Hernandez’s academic career. In 1883, he received a “commercial diploma” and a Gold Medal for Gentlemanly Conduct. In 1885, he received a Bachelor of Science degree, the only degree conferred that year. Throughout his time at the College, he received a number of academic “premiums” in various subjects, including Arithmetic, History, Book-Keeping, Piano, Christian Doctrine, and Navigation. He was a member of the Sodality of the Immaculate Conception of B.V.M. (a Roman Catholic Marian society); the Villanova Debating Society; and the Library and Reading Room Society.

This album provides a glimpse back at a young man’s friendships in the late 19th century. I highly recommend that you take some time to peruse the album yourself in the Digital Library!

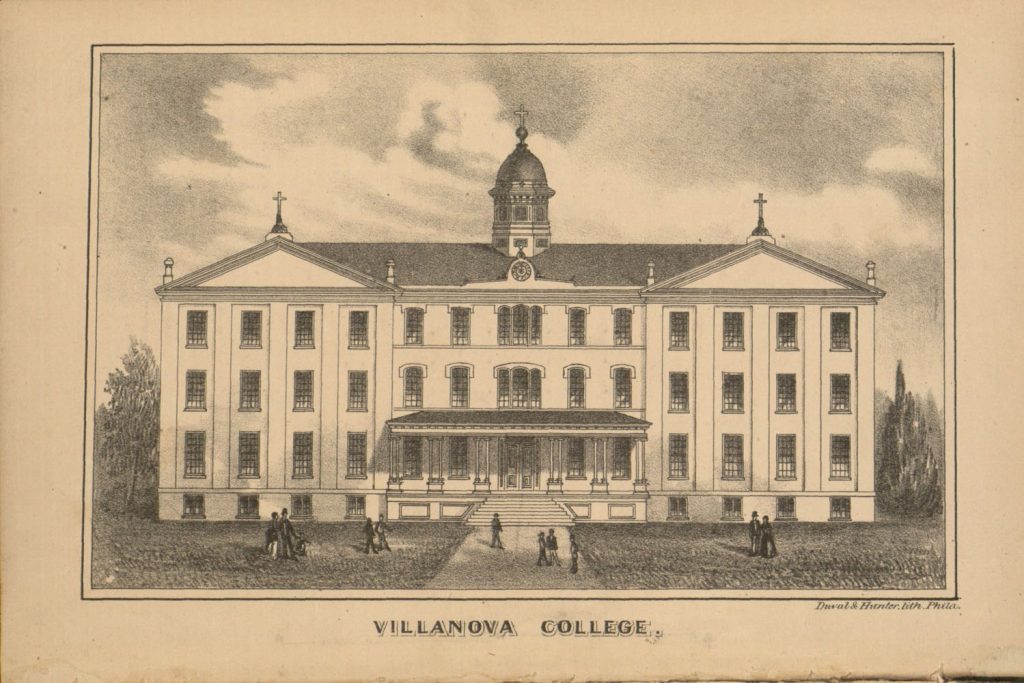

A lithograph depicting Villanova College, published in the 1884-85 College Catalogue.