Posted for Susan Ottignon:

The customary ‘Dear Santa’ letters, written by children every December 24th on Christmas Eve, is a time honored tradition. I encountered 3 such letters, from Mont and Ellie Thackara’s children, when I started transcription work for the Digital Library.

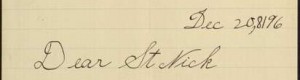

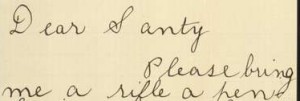

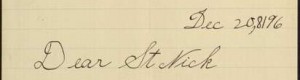

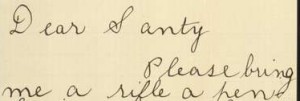

In child-like cursive writing the letters to Santa, by each Thackara child, were penned with unique salutations to the ‘Jolly Old Man,’ and included spelling errors that endear us more to these letters We read from Eleanor’s letter “My dear Santa-Clause,” her brother, Sherman wrote, “Dear St Nick,” with the youngest sibling, Lex ,penned “Santy.” The boys knew Santa’s ‘address’ which they either included in the body of the letter or addressed it directly to him. Santa address, according to Lex, was “Master Santy Clause Up the chimney.” Sherman boldly demanded of St Nick, “Unhitch your horses from the North Pole.”

The ‘wish lists’ penned to Santa by Eleanor, Sherman and Alexander (“Lex) Thackara reflect each child’s deepest longings and are shared by today’s children whether one has been ‘naughty or nice.’ Such things as “a pair of skates and a little iron and iron holder” requested by Eleanor. Sherman wanted Santa to “bring me a sled.” Lex was ‘all boy” when he wrote, “Please bring me a rifle a pen-knife and a kodact.” My guess for Lex’s wish was for a Kodak camera available since 1888.

Alongside the Santa’s letter, tradition beckons children to hang stockings for him to fill with gifts and sweets. The stocking is mentioned in 2 of the letters. Eleanor plainly states:

“. . . fill my stocking full to the brim I am going to hang up an

extra stocking and please fill it to”

Sherman notes his behavior as a good reason for his filled stocking.

“Please fill my stockings very full and do not think me a greedy boy.”

While working on these letters, I marveled over the simplicity of the times and experienced a child’s excitement in the penned letter to Santa on Christmas Eve. I enjoyed transcribing these pieces and many other of the Thackara correspondence. With over a thousand pieces in need of transcription the Sherman-Thackara Collection in the Digital Library has reassured me there many more items to still transcribe.

Here is a link to the Finding Aid for this part of the Sherman-Thackara Collection.

Alex., Sherman & Eleanor S. Thackara to A. M. & E. S. Thackara (parents)

Corresp., 1892-1897, (including 3 letters to Santa Claus):

William T. Sherman Thackara, (1887 – 1983)

Eleanor Sherman Thackara Cauldwell, (1880s? – ?)

Alexander Montgomery Thackara, Jr., (d. December 27, 1921):

7/5/9

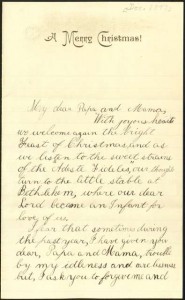

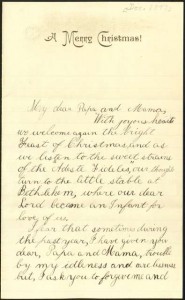

Letter, To: “Dear Papa and Mama” (Ellie and A. M. Thackara) From: “Lex” (A. M. Thackara, Jr.), Christmas 1893.

Xmas blessing to parents by Alex

7/5/10

Letter, To: “My dear Father” (A. M. Thackara) From: “Eleanor” (Eleanor Thackara Cauldwell), Christmas 1893.

Xmas bear story Eleanor

7/5/11

Letter, To: “Santa Claus” From: “Eleanor” (Eleanor Thackara Cauldwell), [December, 1895?].

7/5/22

Letter, To: “Dear Father” (A. M. Thackara) From: “Sherman” (William T. Sherman Thackara), December 1896. Xmas Blessing Sherman

7/5/23

Letter, To: “Santy” From: “Your loving friend Lex” (A. M. Thackara, Jr.), December, [1886?].

7/5/24

Letter, To: “St. Nick” From: “Sherman” (William T. Sherman Thackara), December 20, 1896.