Letters from the Past

Posted for Marjorie L. Haines, Digital Library Intern, Spring 2015

Transcribing historical letters has been one of the most fascinating and enjoyable tasks required in my work with special collections. It generally requires reading personal correspondences from the past and diving into the history of the authors. Imagine a librarian, 100 years from now, reading your descriptive emails home to your parents, your embarrassing facebook messages to your friends, or even those angry texts sent to an ex-lover. What sort of telling anecdotes could be gleaned from your supposedly private conversations?

My first assigned letters to read at Villanova University were those sent from Eleanor M.S. Thackara (“Ellie”) to her father, William T. Sherman [http://digital.library.villanova.edu/Item/vudl:35563; http://digital.library.villanova.edu/Item/vudl:35568; http://digital.library.villanova.edu/Item/vudl:35578]. In her correspondence, Ellie updates her Papa on such events as her recent visit to her mother and the welfare of her own baby. Most prominently seen in this trio of letters, however, are Eleanor and her husband’s plans to move to a new house. It is a costly venture….for which Ellie requests her father’s funding. The manipulation incorporated into these letters strongly reminisces of a child’s request for money from their parents in the modern age. Ellie begins her letters with expressions of adoration for the new residence, which she claims to be both aesthetic and practical in location; she convinces her father that this place is the best option, and what father would not want the best for his daughter? Next, she laments the costs involved with the move and references an offer of financial aid previously made by her father. She does not merely suggest he uphold his promise, but very considerately acknowledges that he may not have the funds or desire to assist in the manner which she proposes. Of course this thoughtfulness would inspire likewise kindness. After receiving confirmation of her father’s agreement to send funds, Ellie requests further finances, by describing her concern that she will have to sell some of her Government Bonds in order to furnish the new home. William must have felt compelled to take care of his darling daughter, based on her response. When it comes to heartfelt thanks, Eleanor excels in expressing herself.

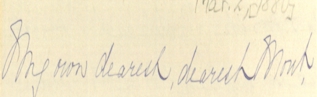

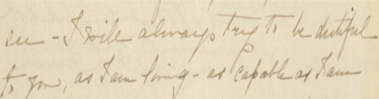

“You will just fix us nicely by sending the surplus check each month. Many thanks. What would we do without our father & friends especially the former.” (Letter, To: “My dear Papa” (William T. Sherman) From: Ellie, October 3, 1881, Back.)

It seems some interactions transcend time.