Transcriptions from the Elizabeth Hayes letters

Posted for Summer 2012 Digital Library Intern Gail Betz:

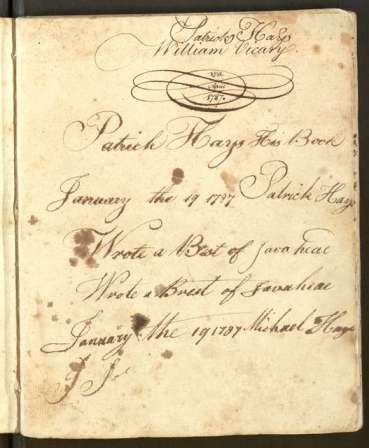

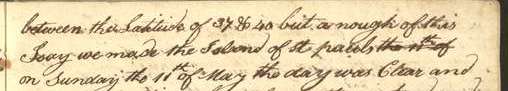

Over the summer, I transcribed a portion of Elizabeth Hayes’s personal letters. Elizabeth was Patrick Barry Hayes’ wife, and she devoted a great deal of her time to corresponding with her seafaring husband and traveling sons. While only a few of the letters that Elizabeth herself wrote are included in the collection, she kept letters from her sons and her husband, which now provide a glimpse into their everyday lives. As a history lover, I greatly enjoyed reading these primary source documents, trying to figure out what the different words could be, and deciphering the context of the letter. I discovered that it was much easier to read the younger sons’ letters, because they had much neater cursive than their father did. It’s possible that Patrick Barry Hayes spent much of his time writing to Elizabeth while at sea, which could account for some of the jarring script that made much of his letters illegible. In contrast, his sons’ handwriting was easy to read, and they used more modern vocabulary than their father did.

Having the opportunity to read personal letters from the early 19th century was fascinating for me. It was like reading a diary, but with multiple perspectives and a great deal of guessing about missing information between dates and locations. I enjoyed learning that one son had reunited with his love, and had written to her father to ask for her hand in marriage. I was worried for the son who was away at school for the first time, was ill, and clearly homesick for his mother. While these letters were written almost 200 years ago, the thoughts and feelings they related were contemporary and relatable.

Thank you to Michael Foight and Laura Bang for sharing their knowledge and advice, and providing me with the opportunity to learn about and work with digital libraries. I enjoyed seeing the “other side” of the digital library process, and look forward to using this experience in future digital projects!

Editorial Note: These transcriptions are in the process of being attached to the digital images and will be available for the public in the near future.