A View from Behind Bars: The Diary of Thomas Lloyd, Revolutionary and Father of American Shorthand, from Newgate Prison 1794-1796.

One of the more interesting and unique items in the Falvey Memorial Library Digital Collection is the diary of Thomas Lloyd (1756–1827) – teacher, stenographer, soldier in the American Revolutionary War and “Father of American Shorthand”. The diary covers the latter half of Lloyd’s incarceration time in London, first at Fleet Prison for debt and later at Newgate Prison for seditious libel against the British government. This item is part of the Lloyd Collection, a subcollection of the American Catholic Historical Society collection hosted at the Villanova University Digital Library.

Born August 14th, 1756 to William and Hannah Biddle Lloyd, Thomas Lloyd first studied shorthand in what is now modern day Belgium at the College of St. Omar. Shortly after, Lloyd immigrated to America right before the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, where he joined the war effort as part of the Maryland Militia Fifth Independent Company. Later, as part of the Maryland Regiment Fourth Company, he was wounded and captured at the Battle of Brandywine (which took place a short drive from Villanova University’s campus). After the war (he was released in a prisoner exchange, recovered in a hospital in Lancaster, PA, and later discharged from the army in 1779), Lloyd used his shorthand skills to record the debates of the Pennsylvania Assembly. Starting in 1787, this work included recording and publishing the debates of the Pennsylvanian Convention to ratify the United States Constitution.

This job led to both note and notoriety, as Thomas Lloyd’s pro-ratification stance was well-known, and reports and rumors abounded of Lloyd taking bribes to help the pro-ratification side. Although Lloyd recorded both pro-ratification and anti-ratification stances, both for the Maryland and Pennsylvanian delegation, the bulk of the speeches that were published were almost always of the pro-ratification kind. Eventually, with the Constitution ratified, Thomas Lloyd attended the First Federal Congress with the goal of recording the entirety of the debates — this job became official when Lloyd was appointed official recorder of the second session of the House of Representatives. The works of Thomas Lloyd during this period, including his notes and published articles, are considered the most accurate representations of the goings-on of Congress during this historic portion of American history.

Visiting family members in London in 1791, he stayed on to help with his father’s business. During his time in London, his desire to familiarize Londoners with the new Republic and its systems led Lloyd to publish “The Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States of America, with the Constitution prefixt” in 1792. Unfortunately, Lloyd also ran into financial difficulties (his London agent failed to make good on his agreements), and Lloyd was arrested and incarcerated in Fleet Prison in London for debt.

While in Fleet Prison, Thomas Lloyd was charged with seditious libel against the British government for posting a placard containing a “declaration of republican principles” on a chapel door. Found guilty, he was sentenced to one hour in the pillory, fined five thousand dollars, and received a three year sentence in Newgate Prison. It was during his prison stay that Lloyd, along with Mathew Carey, a friend and prominent publisher/employee of the Pennsylvania Herald, published “The System of Shorthand Practiced by Thomas Lloyd in Taking Down the Debates of Congress and Now (With His Permission) Published for General Use”. It was this work that made Thomas Lloyd famous for his shorthand style.

Looking for a cure for an ulcer?

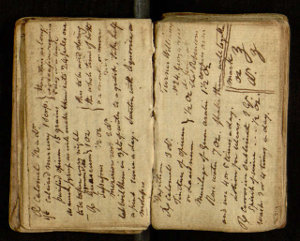

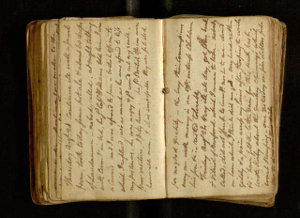

During his time in Newgate Prison, Lloyd kept a diary with near-daily entries on every topic from daily prison life to recipes for medicines to shipping manifests and prices of various goods. The diary reads less like a typical journal of events and thoughts and more like a batch of notes lying haphazard on a desk (or rather more like an engineer’s notepad). This gives the impression the diary wasn’t intended to be published, but rather used as a collection of random notes for things to be remembered in the short-term for later use. An example of this can be seen starting on page 9, where Lloyd, rather than using the space for daily events, lists several recipes in his diary, including some medicinal ones. An example on page 11 has a treatment for ulcers – Lloyd had complained of being ill on several previous pages, which might be the impetus for this entry. As well, entries are written both vertically and horizontally on the page, with numerous scratch-outs, inserts and margin notes. The haphazard style of the diary, while making the pages harder to read, gives the diary the advantage of authenticity – the chance to read the thoughts and notes of someone before they got too heavily filtered for the general public. In addition, the various topics and notes give a more complete picture of the time period and the daily comings-and-goings of both the prison and the outside world.

An interesting item from the diary to those unfamiliar with London prisons is the sheer amount of visitors who call on Thomas Lloyd during his incarceration — it seems like he gets at least one, if not two, visits a day, mostly on either business or legal reasons. These visitors often dine with Lloyd as well. Visits occur frequently enough that Lloyd often makes note of the days without visitors (as well as recording his tendency to get despondent on those days). This is due to the two-tier prison system common in 1790s London – commoners are housed in one section of the prison and have little rights and privileges, whereas more upscale citizens (or at least those with money) are housed in a separate section of the prison and given leeway to have visitors, conduct business, and on occasion even live outside the prison walls. According to the information contained in the diary, Thomas Lloyd is definitely in the latter group.

This of course isn’t to say Lloyd had an easy life in prison – on the contrary, as early as page one Lloyd complains of being assaulted by fellow prisoners as well as being very ill. Lloyd often records not being well over the two years covered in his diary, suggesting that prison sanitation may not be all that great, or that stress was getting the better of his immune system. My own hypothesis on this is that it’s a bit of both.

The 1790s version of drunk dialing…

For historians, lots of historical references are peppered throughout the diary. Two examples: page 171 of the diary notes that Friday, September 11th was the 18th anniversary of the Battle of Brandywine (where Lloyd was wounded and captured by the British) and page 93 has a note on receiving news of the death of Robespierre, the famous figure of the French Revolution (as well as some opinions on the man and his ideals). On a lighter note, head over to page 97, where Lloyd records taking 30 drops of Laudanum (read: opium) for his fever, which may have contributed to his declaration that a British officer “was afraid to kiss [his] posterior” later in the entry.

For those interested in shorthand, the diary has numerous examples of shorthand notation. A good example can be seen on page 107 where Lloyd shortens words that end in “-ought” with “ot”. Lloyd was also known to remove vowels from words in his shorthand, like the word “said” with “s.d”, also seen on page 107.

You can see the diary for yourself, as well as obtain a transcript here in the Digital Library.

“Debtors’ Prison” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 2 April 2011 Web. Apr 2011.

National Shorthand Reporters Association. “Unveiling the Lloyd Memorial Tablet” The National Shorthand Report Vol. 1 No. 9. Sept 1903. Google Books. Web. Apr 2011.

“Newgate Prison” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 10 April 2011 Web. Apr 2011.

“Thomas Lloyd (stenographer)” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 21 November 2010. Web. Mar 2010.

“Thomas Lloyd commonplace book, 1789-1796 Notes” American Philosophical Society. Web. Mar 2010.

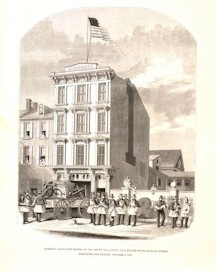

This elaborate presentation, staged by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer on the model of the pageants that were then very popular throughout England and the continent, involved scores of players and dramatized the major events of centuries of our region’s history, from the first glimpse of the Delaware Bay by Henry Hudson to the 1854 consolidation of the old city proper with the 28 surrounding districts into the metropolis we know today. For an entertaining and thorough view back at this amazing event, look no further than the Pennsylvaniana collection of Villanova University’s Digital Library, where a digitized version of the

This elaborate presentation, staged by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer on the model of the pageants that were then very popular throughout England and the continent, involved scores of players and dramatized the major events of centuries of our region’s history, from the first glimpse of the Delaware Bay by Henry Hudson to the 1854 consolidation of the old city proper with the 28 surrounding districts into the metropolis we know today. For an entertaining and thorough view back at this amazing event, look no further than the Pennsylvaniana collection of Villanova University’s Digital Library, where a digitized version of the  Having just spent the summer slogging through H. W. Brands’ sprawling Franklin biography

Having just spent the summer slogging through H. W. Brands’ sprawling Franklin biography  (Manayunk and Germantown from the northwest, Kingsessing and West Philadelphia from the southwest, Tacony, Northern Liberties, and Bridesburg from the northeast, Passyunk from the southeast, etc.) appear, nobly gathering in supplication around a central matronly goddess figure—Philadelphia herself. Interspersed throughout the script are color plates of costumes designed for the production: British Redcoats, French Gentlemen, and Marie Antoinette, among others.

(Manayunk and Germantown from the northwest, Kingsessing and West Philadelphia from the southwest, Tacony, Northern Liberties, and Bridesburg from the northeast, Passyunk from the southeast, etc.) appear, nobly gathering in supplication around a central matronly goddess figure—Philadelphia herself. Interspersed throughout the script are color plates of costumes designed for the production: British Redcoats, French Gentlemen, and Marie Antoinette, among others. Particularly interesting are the many photos and drawings of the factory buildings used by these companies; considering the huge number of abandoned buildings in present-day Philadelphia, the ads in this book could provide valuable guidance for students of Philadelphia architectural history.

Particularly interesting are the many photos and drawings of the factory buildings used by these companies; considering the huge number of abandoned buildings in present-day Philadelphia, the ads in this book could provide valuable guidance for students of Philadelphia architectural history.