Pugilists, poetry, and prose for Black History Month

Black History is not a particular focus of our Special Collections department, but we do have a few noteworthy items with which I was able to put together a small exhibit on the first floor of the library. Only one of these books is available in our Digital Library, but the others are available through the Internet Archive. Here, then, is a brief look at some of these historically interesting books.

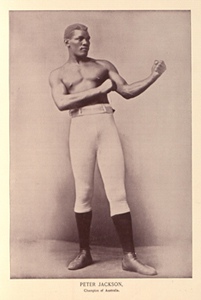

The portrait gallery of pugilists of America and their contemporaries by Billy Edwards (Philadelphia: Pugilistic Pub. Co., 1894) profiles many of the noteworthy boxers of the late nineteenth century. Although the majority of pugilists included in the book are white, the book gives a good view of the racial tensions in boxing at the end of the nineteenth century. One of the black boxers profiled in the book is Peter “Black Prince” Jackson (1861-1901). The descendant of a freed slave, he was an Australian heavyweight boxer who had a significant international career, although the Australian Dictionary of Biography Online notes that “Jackson was one of the finest boxers never to fight for a world championship: John Sullivan refused to defend his title against a black and [James J.] Corbett avoided Jackson once he gained the heavyweight crown in 1892.” For more on Jackson’s career as “a black fighter in a white world,” see the full article here.

Hampton and its students by two of its teachers, Mrs. M.F. Armstrong and Helen W. Ludlow (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1875), tells of the founding of the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in 1868, shortly after the conclusion of the U.S. Civil War, by black and white leaders of the American Missionary Association. The roots of this school went back further, however, to a “simple oak tree” on a former plantation that served as a gathering place for former slaves who sought refuge there with the Union Army in 1861. One of the school’s earliest students was Booker T. Washington, who arrived in 1872 at the age of 16, and later became a renowned educator and author. Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute shortened its name in 1930 to Hampton Institute, and in 1984 it was accredited as Hampton University.

Poems of cabin and field by Paul Laurence Dunbar (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1900) includes poems in dialect by Dunbar paired with photographs from the Hampton Institute camera club. Dunbar was the first African American poet to win national acclaim. He was born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1872, to former slaves. Dunbar’s work included poems in dialect as well as standard English, essays, short stories, and novels. His work often described the difficulties faced by African Americans as they tried to achieve equality. To read more about Dunbar’s life and work, see the University of Dayton’s Paul Laurence Dunbar Website.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe (Cleveland: J. P. Jewett & Company, 1852) is one of the most widely-known novels about slavery. Published in 1852, this novel focuses on the character of Uncle Tom, a long-suffering slave, around whom the other characters’ stories revolve. The novel portrays the reality of slavery while also emphasizing that Christian love can overcome anything, even the enslavement of fellow human beings. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the best-selling novel of the nineteenth century, selling 300,000 copies in the United States in its first year of publication. The novel was heavily criticized by those who supported slavery, especially in the South, while it received praise from abolitionists. In response to such negative criticism, Stowe produced A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Boston: J. P. Jewett & Co., 1853) one year after Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Stowe maintained that she based her novel on the stories of fugitive slaves she encountered in Ohio. This book was also a best-seller.

Uncle Remus, his songs and his sayings: the folk-lore of the old plantation by Joel Chandler Harris (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1881) was a collection of animal stories, songs, and other forms of oral folklore that were compiled into written form by Harris, who remembered hearing them from slaves while he worked on a plantation as a young man. The stories are rendered in Harris’s version of a Deep South slave dialect. Br’er Rabbit is the main character of many of the stories. He is a trickster, often getting himself into scrapes with Br’er Fox and Br’er Bear. The stories often convey a lesson, much like Aesop’s Fables.

Both Harriet Beecher Stowe and Joel Chandler Harris were white Americans who wrote stories about African Americans and slavery. First published in the latter half of the nineteenth century, both authors were praised by their contemporaries for the accuracy of their depiction of African Americans in what was then considered to be a non-racist manner. Although attitudes have changed since then and the stereotypes and dialects of the stories are now deemed offensive, Stowe and Harris both remain important and influential figures. Stowe’s work helped to fuel the abolitionist cause and, according to some, was also an influence leading up to the Civil War. Harris’s Uncle Remus tales were an accurate recording of tales told by slaves, which helped to preserve their folklore for future generations.