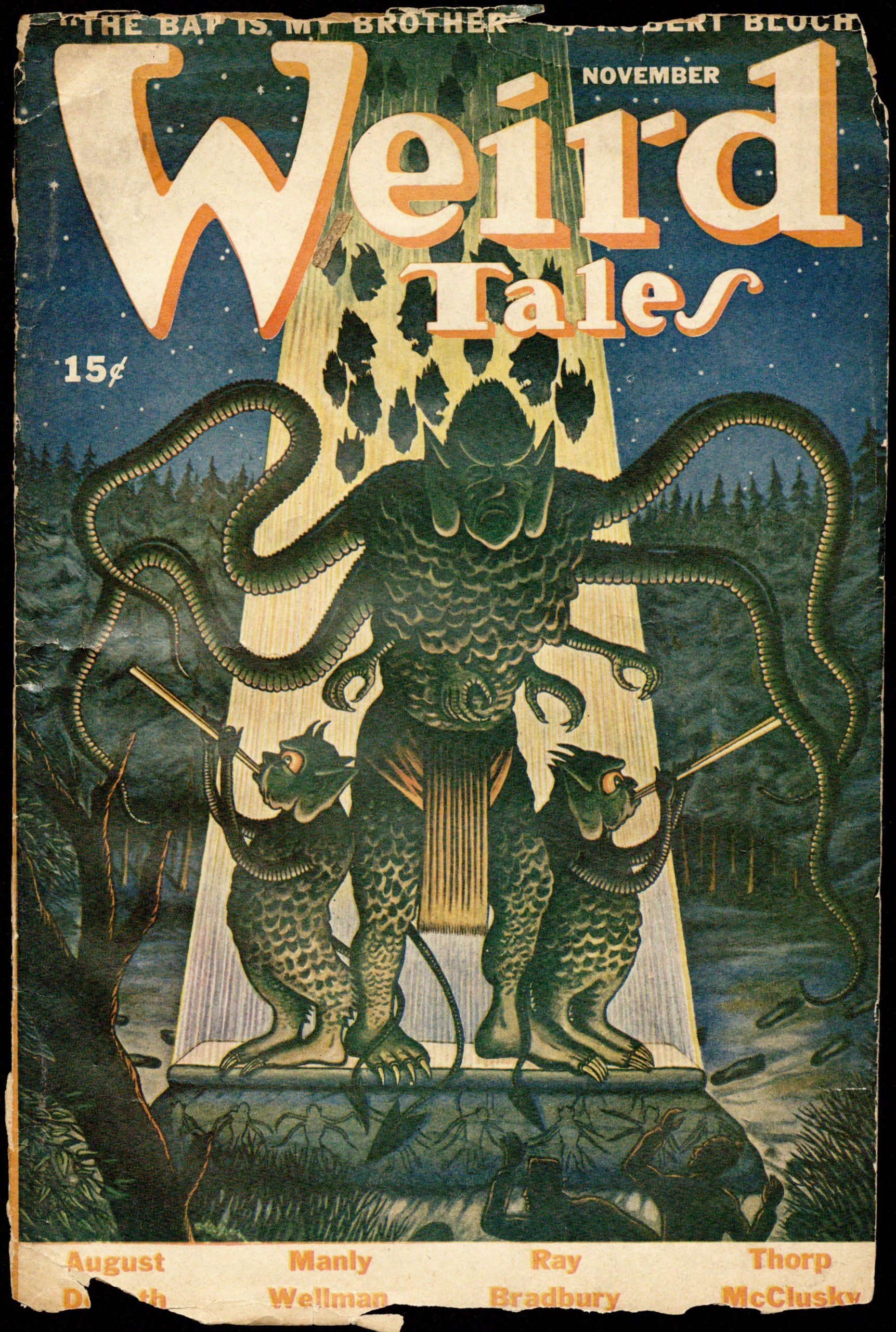

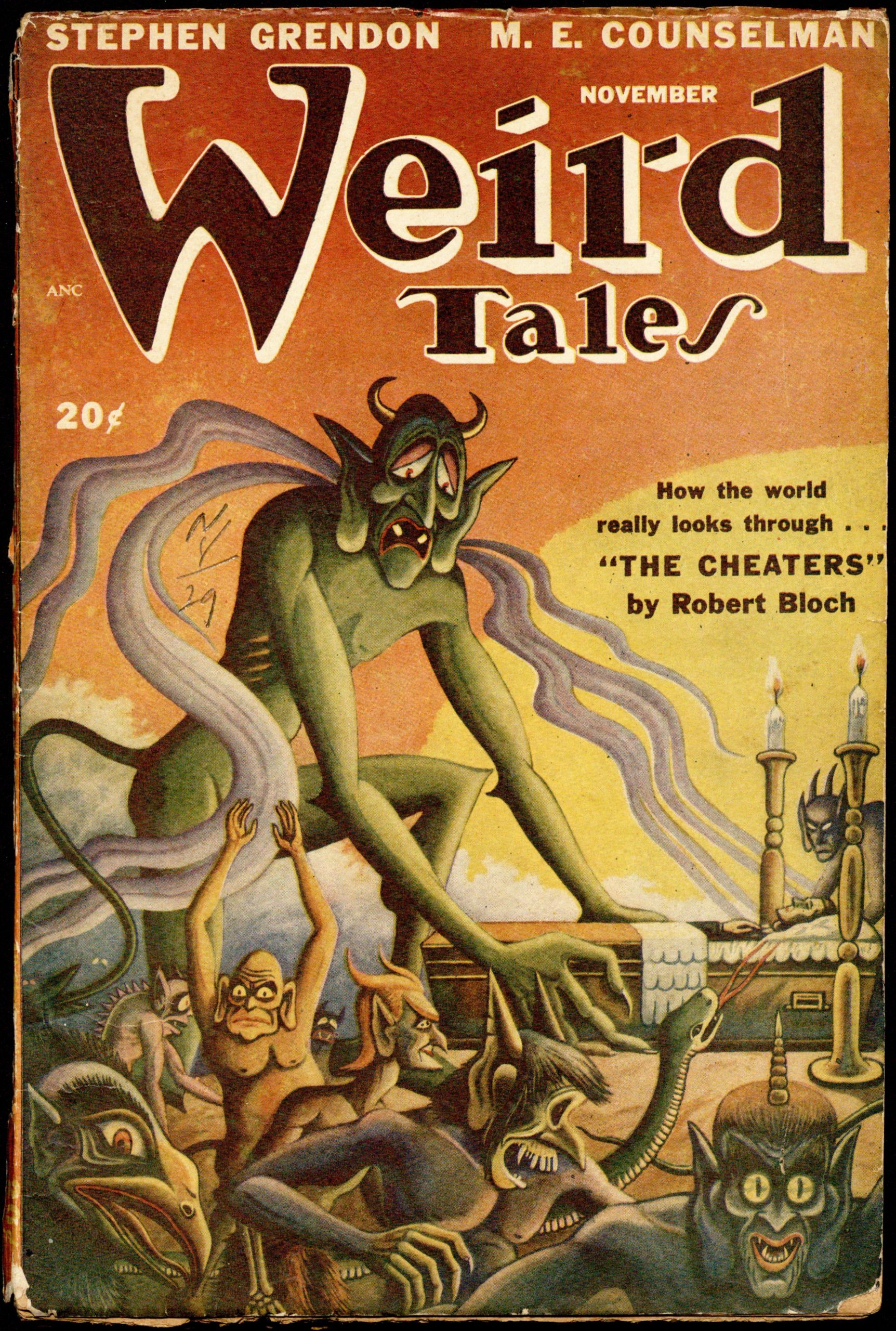

Falvey Library’s Distinctive Collections and Digital Engagement (DCDE) department recently received a generous donation of dime novels and other popular culture materials, including comic books drawn from the collections of John Randolph “Randy” Cox. Randy was a highly regarded scholar and collector, with expertise in numerous areas of pulp literature, including Nick Carter and Sherlock Holmes. He was also an early supporter of the Edward T. LeBlanc Dime Novel Bibliography project, a comprehensive online database of dime novels, story papers, reprint libraries, and related materials hosted by Falvey Library. Among the titles recently donated from Randy’s collections are several comic books published by Marvel Comics in the 1960s and 1970s. These materials demonstrate the value of collecting original copies of comic books in special collections.

-

-

Captain America Vol 1 #110, February 1969

-

-

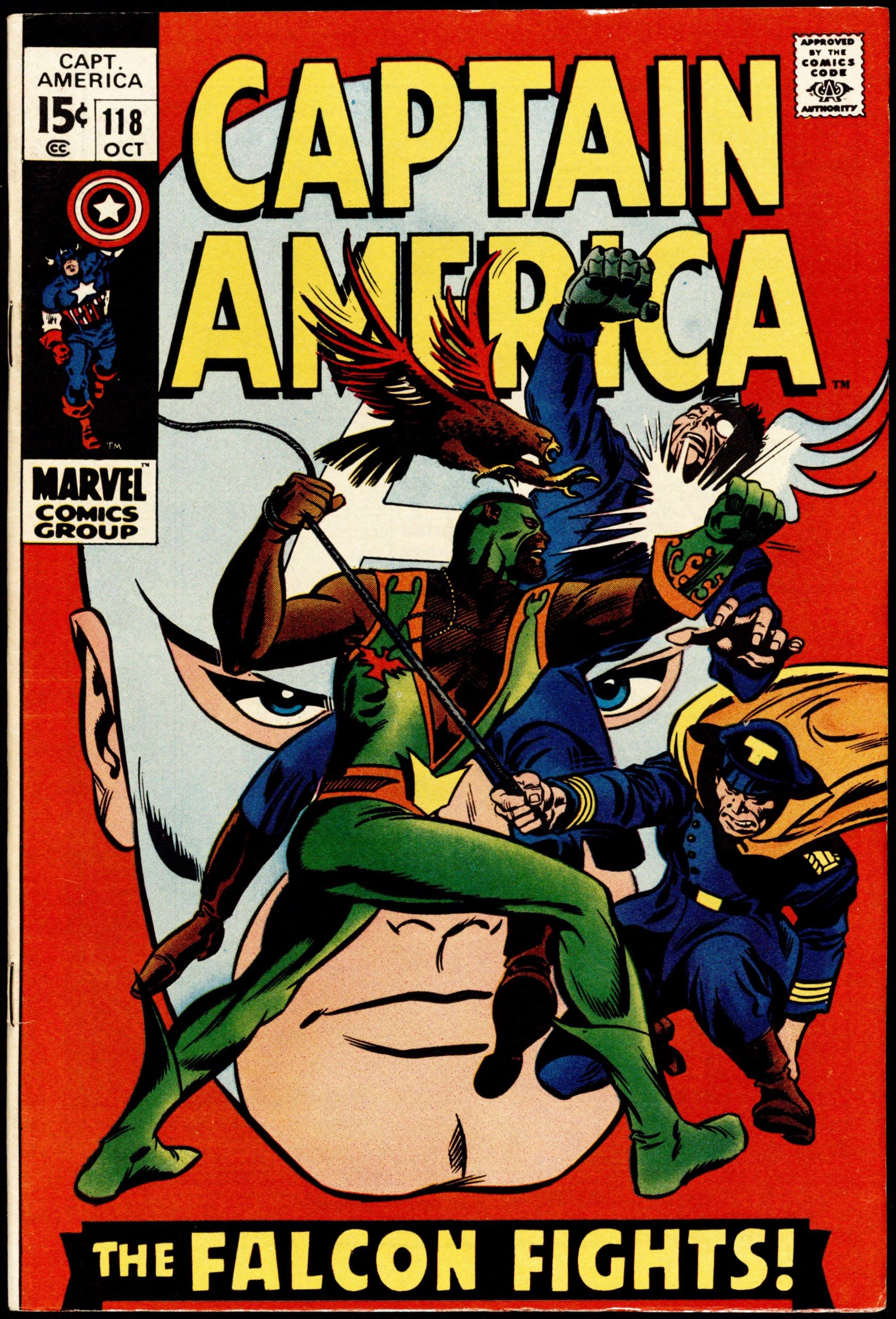

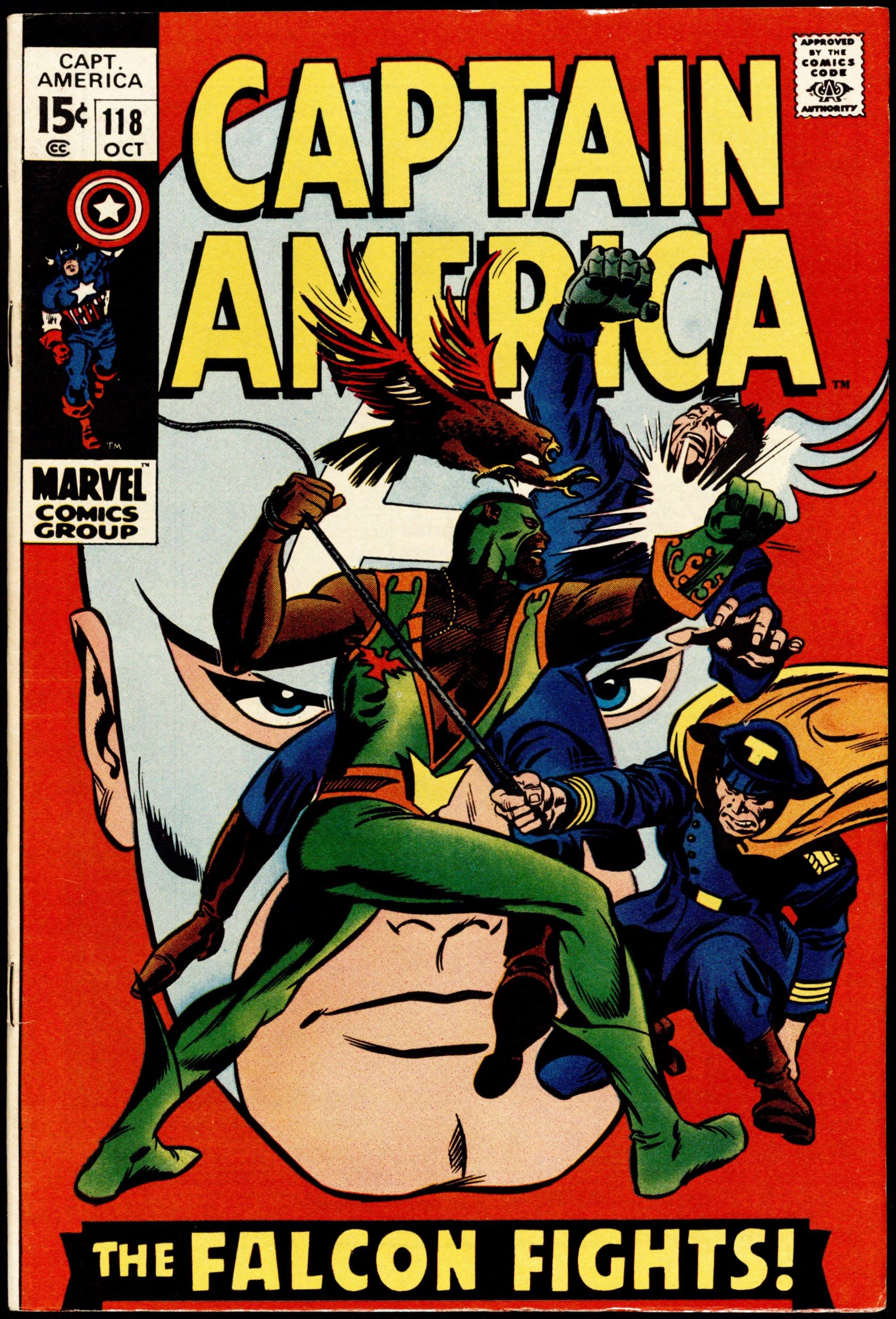

Captain America Vol 1 #118, October 1969

-

-

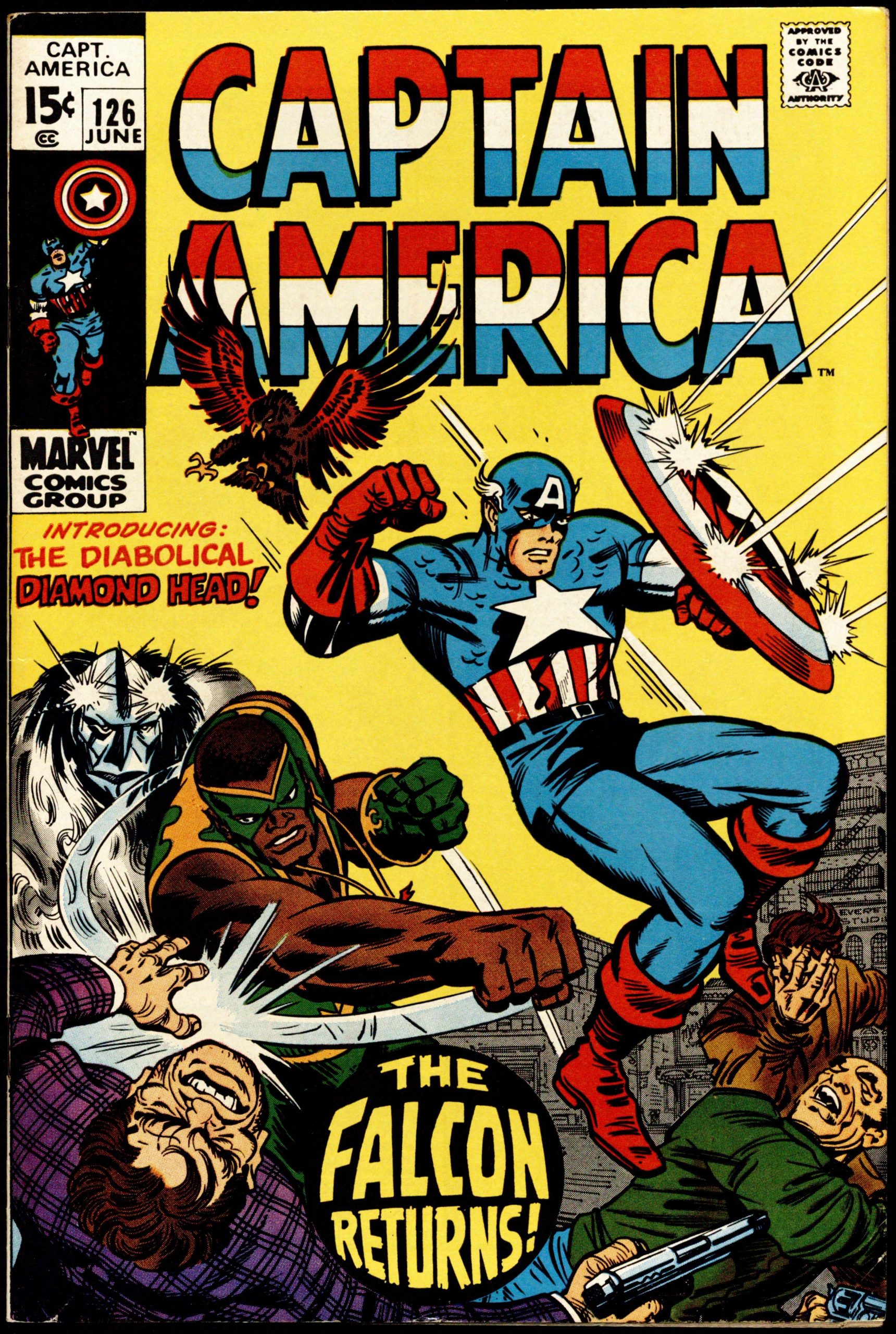

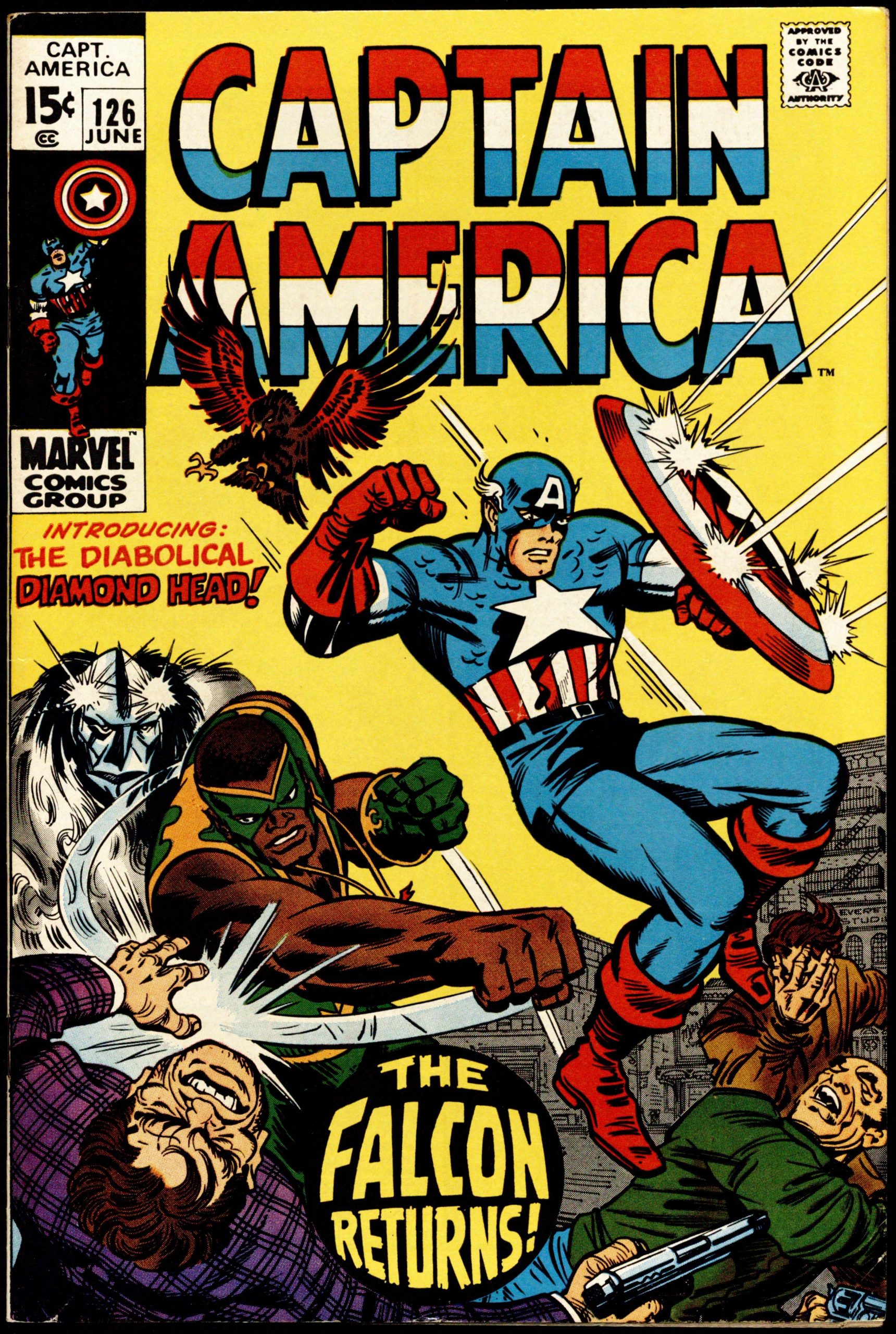

Captain America Vol 1 #126, June 1970

-

-

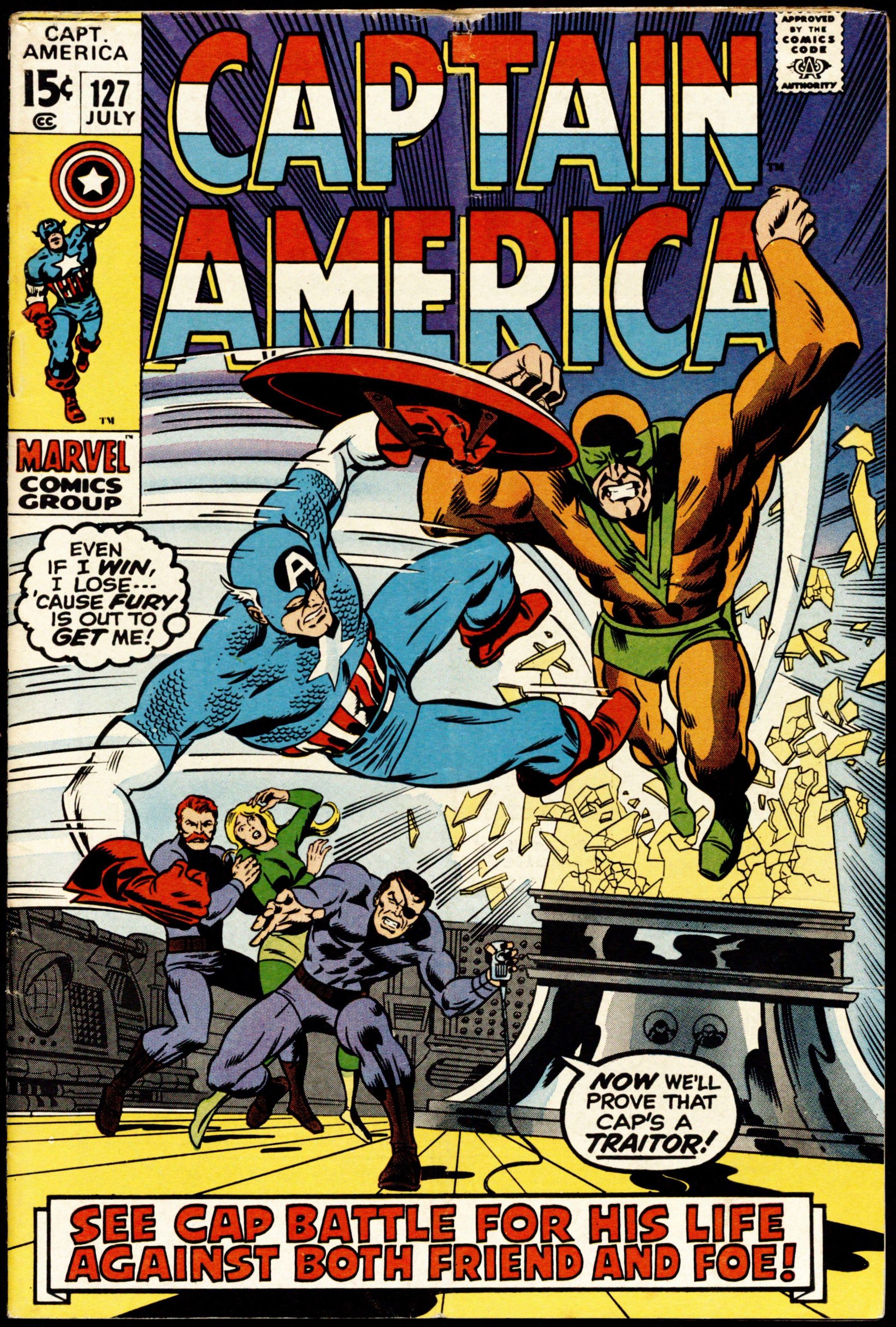

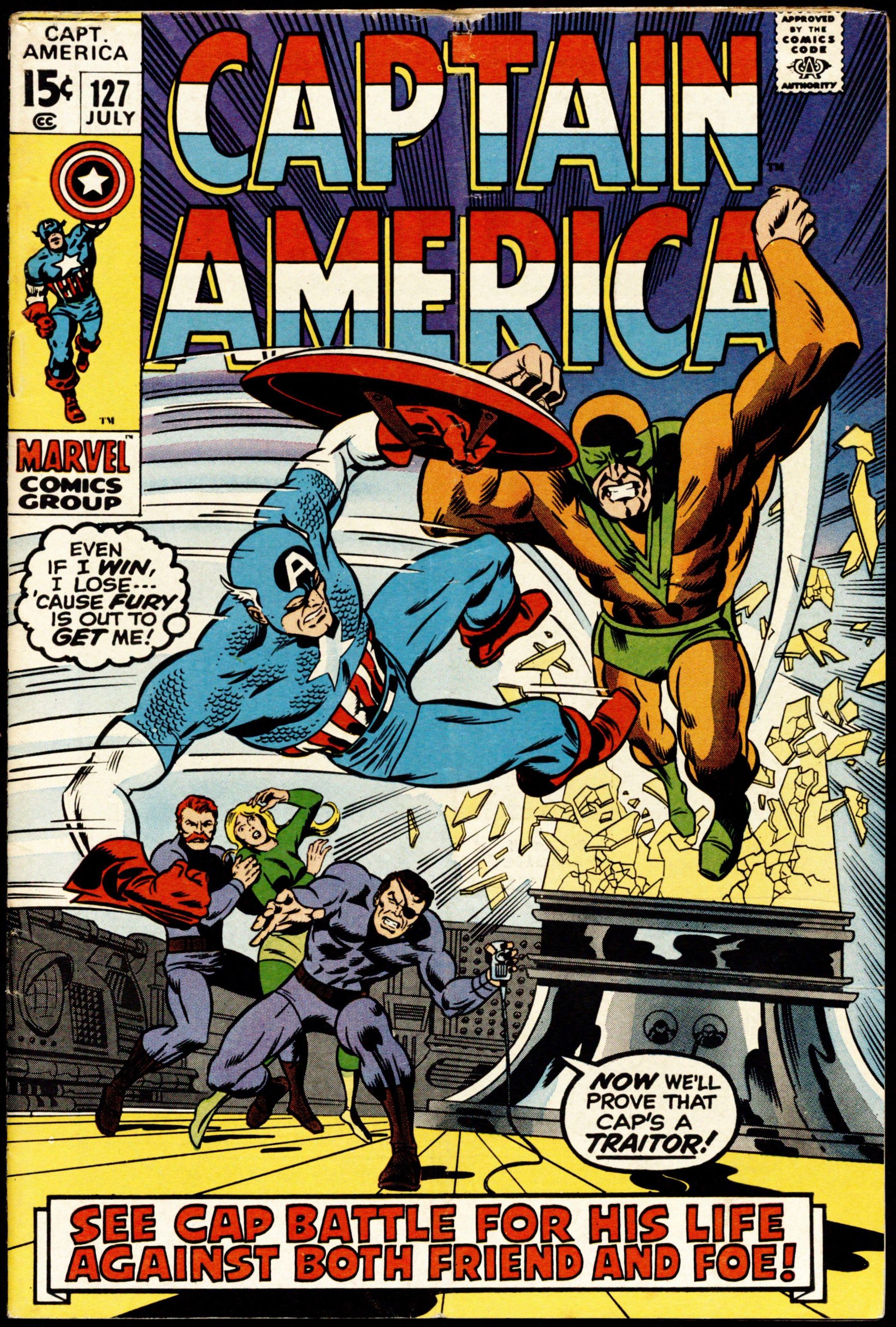

Captain America Vol 1 #127, July 1970

-

-

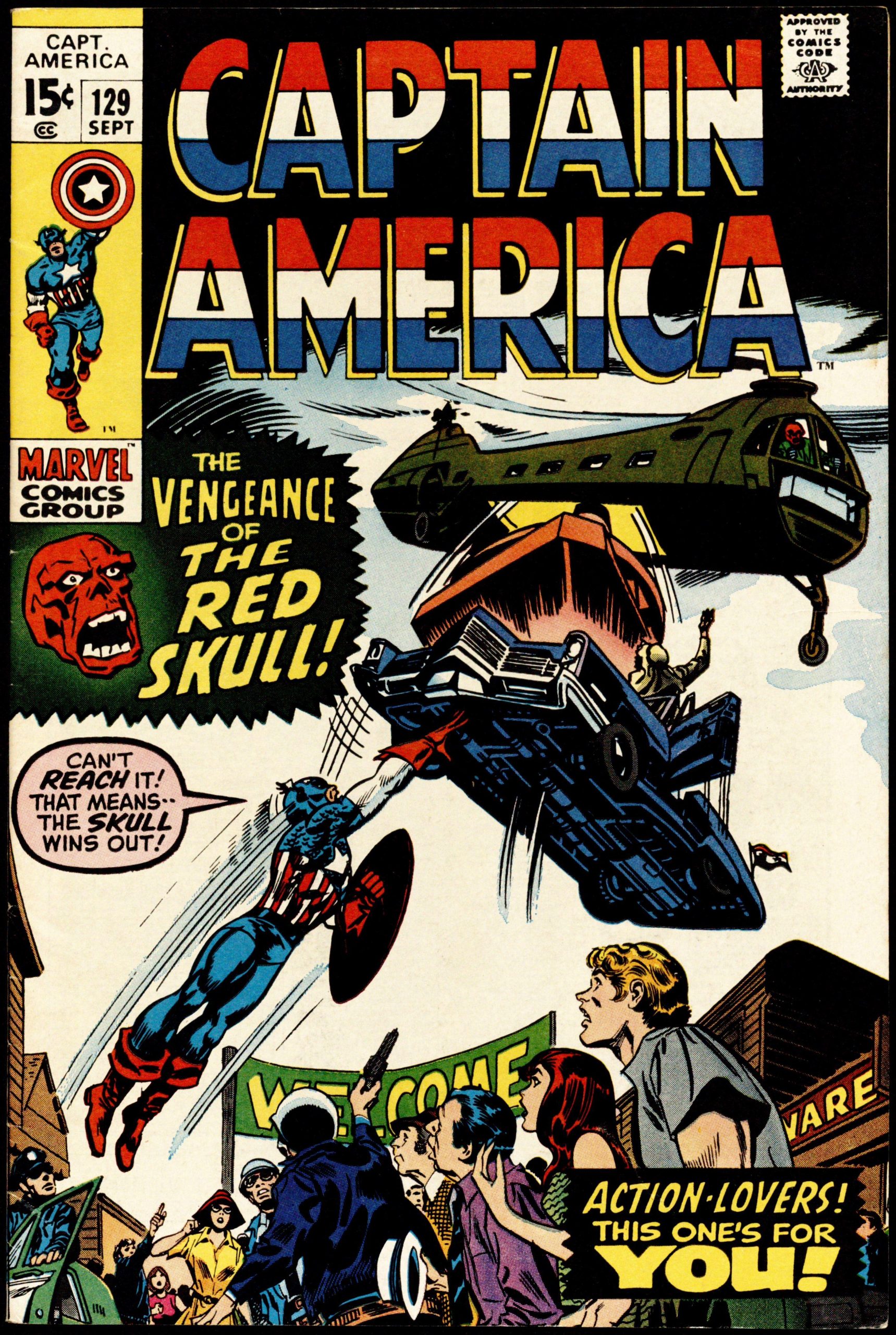

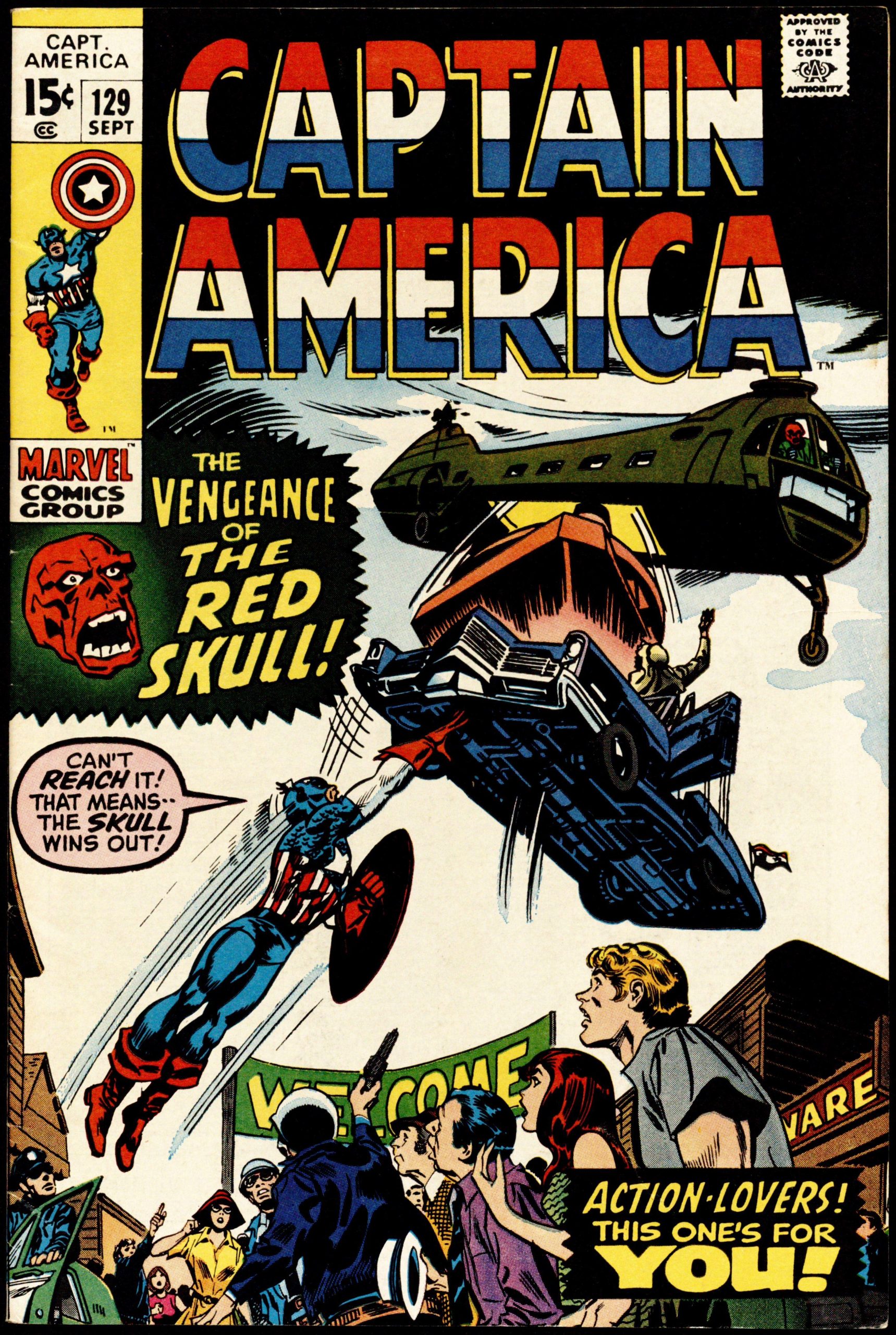

Captain America Vol 1 #129, September 1970

-

-

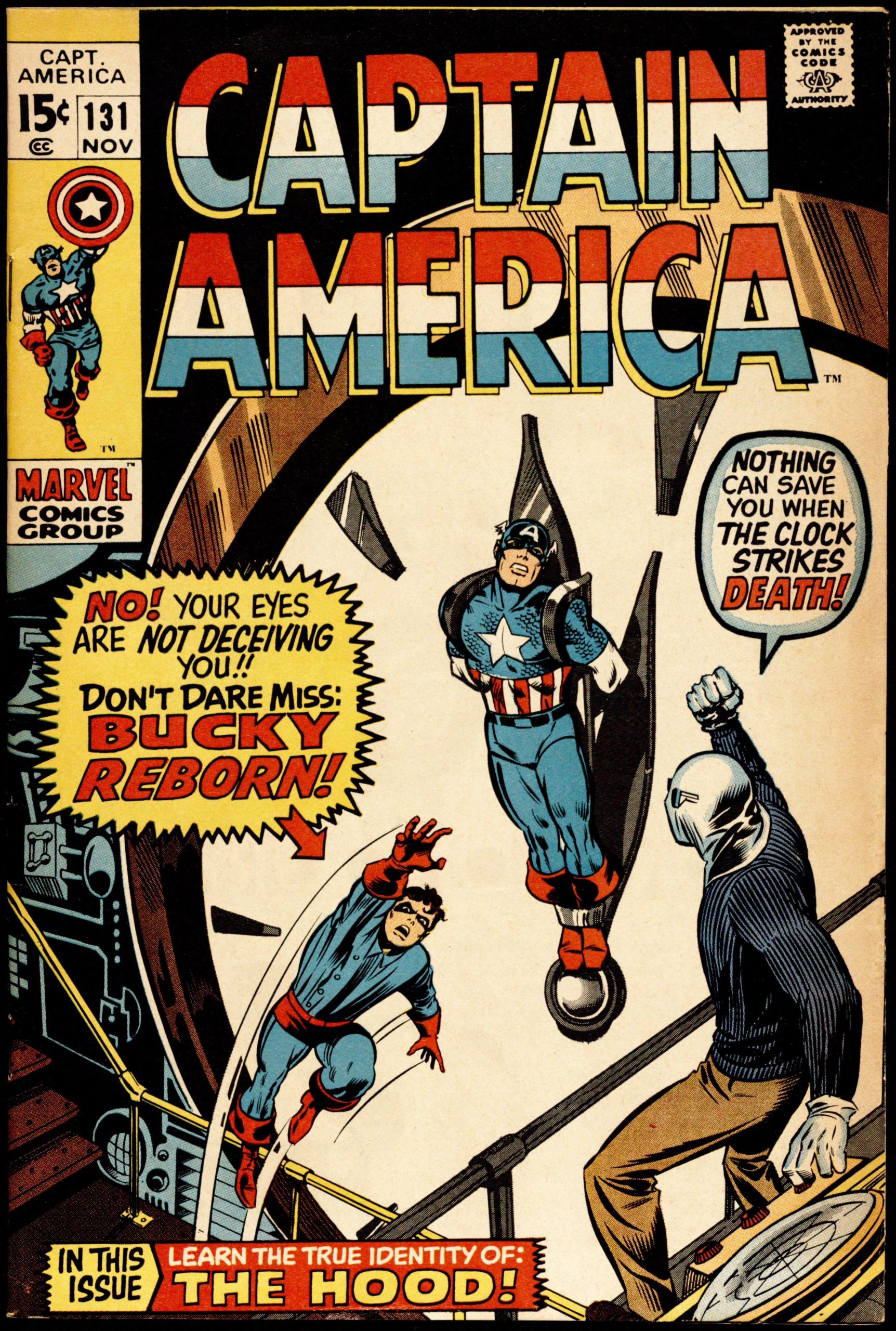

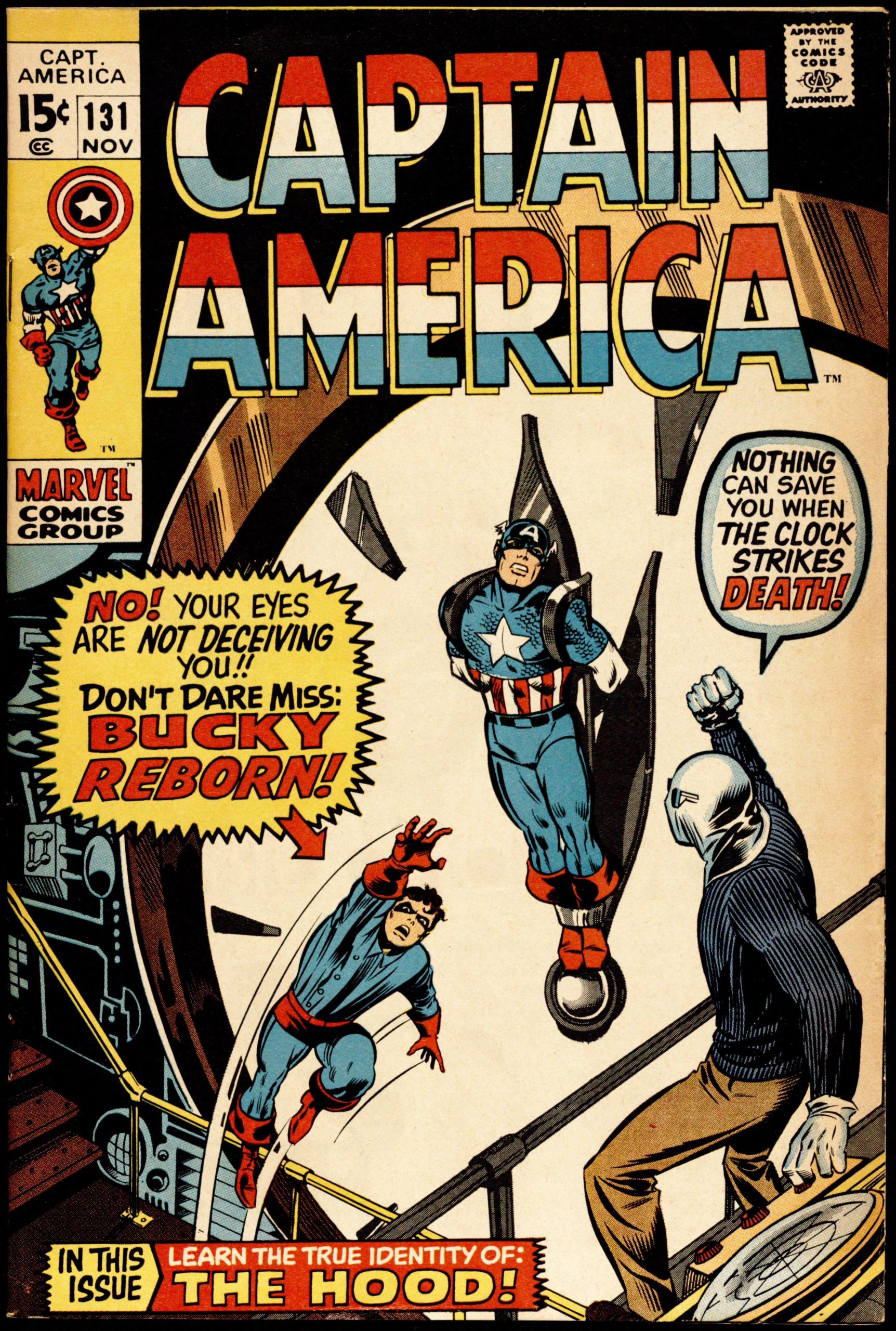

Captain America Vol 1 #131, November 1970

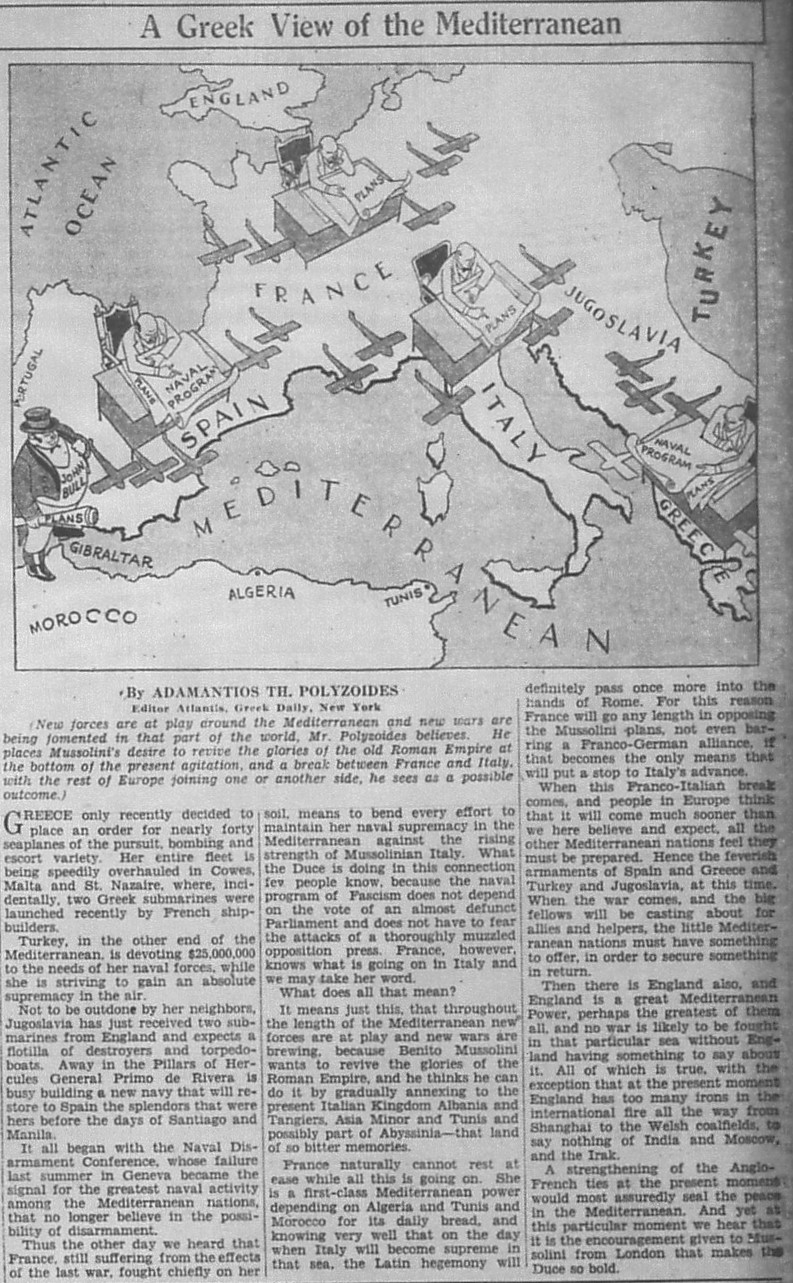

Some Brief History

Under the banners of Timely Comics and Atlas Comics, Marvel Comics published stories in various genres from the 1930s to the 1950s, a period known as a Golden Age of comic books. It was during this period that a handful of now-classic characters, such as Captain America and Namor the Sub-Mariner, were introduced to readers. However, it was not until the Silver Age of the 1960s and 1970s that Marvel would become synonymous with the superhero genre. This was largely owing to the humanizing of superheroes: While characters published by DC Comics (Marvel’s main competition, then and now) like Superman and Wonder Woman were akin to gods, Marvel characters experienced more grounded, personal problems alongside their grandiose, world-saving pursuits. For example, Spider-Man struggled to make rent and stressed about his coursework. Some of the creators responsible for ushering in this era of storytelling (most of whom created the Captain America comics pictured above) were Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Sal Buscema, Don Heck, Jim Steranko, Gene Colan, John Romita Sr., Art Simek, Sam Rosen, and Stan Lee.

Detail from Captain America Vol 1 #106, October 1968. Art by Jack Kirby.

Creators such as these often worked in highly specialized roles, which were necessitated by the fast-paced nature of the comics industry, as well as the complexity of developing graphic storytelling. American comics typically involve a writer who develops the plot; a penciller who designs the panel layouts and draws the initial sketches; an inker who finalizes the penciller’s work by tracing it in black ink; a colorist who adds color to each page; a letterer who inserts speech bubbles and designs fonts and logos; and an editor who oversees and double-checks the whole process. There can be much variation to this process, but it has remained relatively consistent throughout the decades, even while several steps are now accomplished digitally in most cases. What made Marvel’s procedures unique during the Silver Age, however, was the emergence of the “Marvel method” of creating comic books, in which the penciller arguably played a more central role than the writer in developing narratives. Following the Marvel method, a writer would come up with rough outlines for a story, without providing detailed dialogue or many details about where individual scenes were set. This would allow the penciller to make major decisions regarding setting, pace, and other aspects of the story, making the penciller’s role similar to that of a film director. The writer would then write the narration and dialogue around the penciller’s drawings. Most comics creators have not been using the Marvel method since the turn of the century. Nonetheless, there are still some who prefer it, such as popular penciller Greg Capullo, who, though he works at DC Comics and Image Comics, began his career at Marvel in the late 1980s.

Relevance to Special Collections

Partly due to the success of superhero film franchises like the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), comic-book superheroes have seen a resurgence in popular culture during the past decade. Stories that have now become a mainstay in the popular imagination, like the MCU’s Infinity Saga, can be traced back to comics published in the late twentieth century. For example, “the tesseract,” a cosmic weapon/energy source used by the villain Red Skull in the film Captain America: The First Avenger (2011), and later by Loki in The Avengers (2012), makes an early appearance in an issue held by Falvey’s Distinctive Collections, under the name of “the cosmic cube”:

-

-

Captain America Vol 1 #115, July 1969

-

-

Detail from Captain America Vol 1 #115, July 1969

This newfound popularity of Marvel characters has meant that older comics, such as the ones in Falvey’s Distinctive Collections, are easy to find and rarely out of print. Even when they are out of print, there is always the option of accessing a digital copy. However, most recent editions of twentieth-century comics display several differences from the original copies. These differences demonstrate the value of collecting original copies of these comics in heritage institutions.

-

-

Detail from Captain America Vol. 1 #110, original copy

-

-

Detail from Captain America Vol. 1 #110, modern reprint

-

-

Detail from Captain America Vol. 1 #110, original copy

-

-

Detail from Captain America Vol. 1 #110, modern reprint

-

-

Detail from Conan the Barbarian Vol 1 #1, original copy

-

-

Detail from Conan the Barbarian Vol 1 #1, modern reprint

When large companies like Marvel reprint their earlier titles, they usually recolor the drawings. The above images show the differences between several panels in the copies of Captain America Vol 1 #110 and Conan the Barbarian Vol 1 #1 held at Falvey and their modern reprints (you may click on all images in this article to enlarge them). While some may argue that the modern edition is superior due to its cleaner lines and brighter colors, it does not teach us much about comic-book authorship or readership in the Silver Age. From an artistic point of view, it could be argued that the relatively muted colors and imprecise inks of the original printing are better suited to the art style. Moreover, the signature “dots,” which marked the cheap mechanical printing processes of the time, lend a realistic texture to many parts of the page. On the contrary, the flat recoloring makes figures and environments stand out in a way that was not originally intended. Artists and editors designed these comics with specific printing technologies in mind. If a researcher is to study these titles, they will get a clearer understanding of the comics in their moment of creation if they examine original copies.

-

-

Fan mail section in Captain America Vol. 1 #129, September 1970

-

-

Fan mail section in Tales of Suspense Vol 1 #89, May 1967

-

-

Fan mail section in Conan the Barbarian Vol 1 #1, October 1970

-

-

Fan mail section in Ka-Zar the Savage Vol 1 #20, November 1982

Another aspect that is omitted when older comics are reprinted (except in facsimile editions of key issues) is the section of letters, or “fan mail,” at the end of each issue. These sections, which still exist though not as frequently as they used to, often have pun-based titles and publish selected letters from readers, as well as responses from Marvel’s editorial staff. They shed light on the reactions and attitudes of these comics’ first readers. One notable characteristic is that Marvel did not seem to shy away from publishing fan letters that were critical of the company or the topics explored in superhero comics. For instance, the following fan letter, published in Captain America Vol 1 #126 (the plot of which addresses issues of racial inequality), is actively resistant to the types of nationalistic attitudes that a character like Captain American might risk inadvertently endorsing:

Fan letter from Captain America Vol 1 #126, June 1970

A similarly valuable paratextual segment in Marvel comics of this era is “Stan’s Soapbox,” where writer and editor Stan Lee would discuss a wide variety of topics in his characteristically jovial style. (Lee, whom many will recognize as an elderly man who made brief appearances in most Marvel films until his passing in 2018, was as much a showman as a comics creator–so much so, in fact, that when artist Jack Kirby left Marvel Comics, he created a satiric parody of Lee for DC Comics called Funky Flashman.) The following two entries of “Stan’s Soapbox,” published in consecutive issues of Captain America, show the editorial staff’s active engagement with readers’ opinions:

-

-

“Stan’s Soapbox” entry in Captain America Vol 1 #106, October 1968

-

-

“Stan’s Soapbox” entry in Captain America Vol 1 #107, November 1968

Some entries in “Stan’s Soapbox” would also offer glimpses into the process of creating comics, including the Marvel method. Other entries announced events that would become key moments in comics history, such as Jack Kirby leaving Marvel.

“Stan’s Soapbox” entry in Captain America Vol 1 #127, July 1970

“Stan’s Soapbox” entry in Captain America Vol 1 #129, September 1970

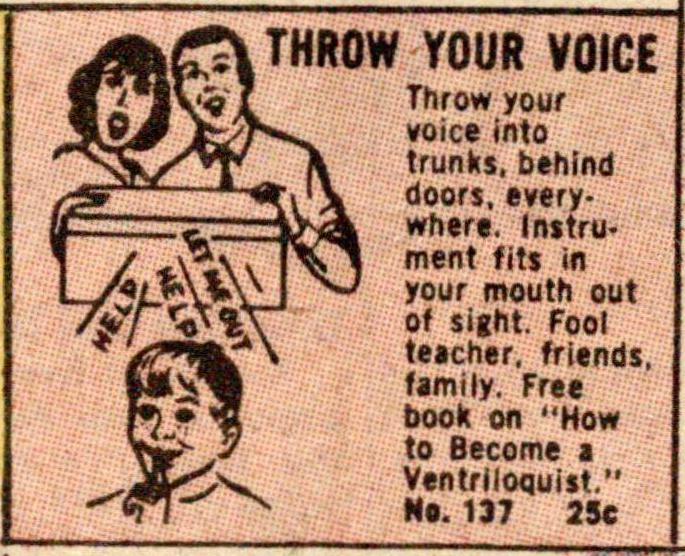

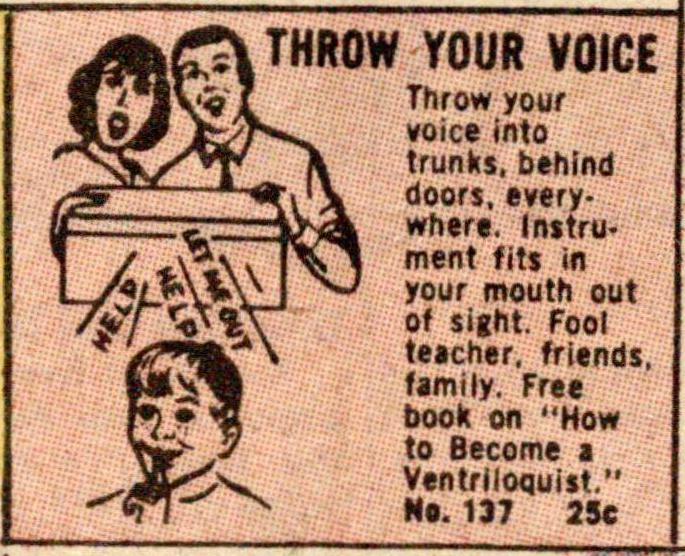

Another element that almost never makes its way into modern reprints is the impressive and sometimes bizarre variety of advertisements that accompanied these superhero stories. Some addressed (or, unfortunately, sometimes took advantage of) the anxieties and insecurities of readers, such as the advertisement below about reading proficiency. Others promoted interesting and strange products, such as a book that teaches readers to throw their voices like a ventriloquist.

Advertisement in Captain America Vol 1 #107, November 1968

Advertisements in Captain America Vol 1 #107, November 1968

Advertisement in Captain America Vol 1 #107, November 1968

And, of course, some advertisements would announce the publication of new Marvel series, such as the 1970 series featuring Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian, the first comic book published in the United States to feature this famous character.

Advertisement in Captain America Vol 1 #129, September 1970

Advertisement in Ka-Zar the Savage Vol 1 #20, November 1982

Collectively, these advertisements and other paratextual segments mentioned above help us understand the interests, attitudes, and even spending habits of readers during the late twentieth century. (For similar information on early-twentieth century consumers, see a 1916 store catalog recently made available on the Villanova Digital Library.) They can serve as invaluable resources for research; and, this research can only reach its full potential if researchers have access to original copies of these comic books, rather than being limited to modern reprints.

However, the world of comic-book collecting can be difficult to navigate for those not already familiar with it. Moreover, key issues (i.e., issues that include the first appearance of a major character or a particularly famous moment in a widely beloved story) can be too expensive for most individuals to afford. In an especially extreme case, a copy of Action Comics #1–the first appearance of superman and the birth of the superhero genre as we know it today–sold for $3.18 million last year. However, this case is not reflective of the prices of most older comic books, which are indeed affordable for many heritage institutions. By collecting original copies of comic books, heritage institutions can make these texts accessible to researchers and fans alike. Furthermore, these comics are recent enough to have copyright restrictions, which is why they have not been digitized for the Villanova Digital Library. In most cases, only modern reprints have been made available digitally by Marvel and other major companies. This is yet another reason for heritage institutions to collect physical copies.

-

-

Tales of Suspense Vol 1 #89, May 1967

-

-

Captain America Vol 1 #107, November 1968

-

-

Human Torch Vol 2 #5, May 1975

The series referenced in this article are part of the growing number of comic books in Falvey’s Distinctive Collections. Be on the lookout for additional blog articles that highlight these comics, their value of research, and their connections to other historical materials at Falvey and beyond. In the meantime, if you are interested in a primer on how to study and appreciate comic books, then make sure to check out Falvey’s copy of Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (1993).

![The Saturday Evening Post, v. VII, no. 372, September 13, 1828, p. [3].](https://blog.library.villanova.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/default-1.jpg)

![The National Gazette and Literary Register, v. 4, no. 390, Tuesday, August 26, 1823, p. [1].](https://blog.library.villanova.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/default-3.jpg)

![The National Gazette and Literary Register, v. 4, no. 394, Thursday, September 4, 1823, p [4].](https://blog.library.villanova.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/default-4.jpg)

![Boston notion, v. II, no. 24, Saturday morning, March 13, 1841, p. [1].](https://blog.library.villanova.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Boston-notion-v.-II-no.-24-Saturday-morning-March-13-1841-p.-1-733x1024.jpg)

![Mystery stories, v. XIII [sic XII], no. 3, December, 1927, front cover.](https://blog.library.villanova.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Mystery-stories-v.-XIII-sic-XII-no.-3-December-1927-front-cover-220x300.jpg)

![Mystery stories, v. XIII [sic XII], no. 3, December, 1927, p. 344.](https://blog.library.villanova.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Mystery-stories-v.-XIII-sic-XII-no.-3-December-1927-p.-344-194x300.jpg)

![Mystery stories, v. XIII [sic XII], no. 3, December, 1927, p. 345.](https://blog.library.villanova.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Mystery-stories-v.-XIII-sic-XII-no.-3-December-1927-p.-345-208x300.jpg)

![Cover for "Saved by a Phantom," [1800s]. Click on image for full text.](https://blog.library.villanova.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/3-715x1024.jpg)